Portugal and the Jews

Moisés Espírito Santo[1] goes as far as to defend the thesis according to which pre-Roman language, religion, toponymy, and other civilizational traits of Iberian people would stem from Phoenician and Canaanite, namely Hebrew/Jewish origins. This would contrast with Islamic vestiges that would be practically non-existent in religious traditions and a lot less than widely assumed in current Portuguese language.[2]

According to Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos, the first Jews arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in the 1st century AD, after the Romans destroyed the 2nd Temple of Solomon (70AD). “Recent archaeological excavations in Mértola [south of Portugal] have revealed a gravestone dating from the 5th century and showing a menorah, which means that it must have belonged to the Jewish community which lived alongside the Visigoths, Romans and Arabs, long before the foundation of the kingdom of Portugal.

At the time of the so-called Christian Reconquest, while the Arabs fled or saw their power structure crumble, the Jews decided to stay on, and they continued to occupy important positions at the courts of the first Portuguese kings, as is confirmed by documents of the time.

In Portugal, they worked in a wide range of professions: as manufacturers, land-owners or farmers, spreading gradually throughout the whole country, they were also easily identifiable in the ‘intellectual’ professions: astrologers, mathematicians, translators, printers and booksellers, philosophers, physicians and financiers. They were also part of the Court elite, and were very much in evidence in preparing for and undertaking the Voyages of Discovert.

The Expulsion Decrees of 1492 (Spain) and 1496 (Portugal), forced conversion and the creation of the Portuguese Inquisition (1536) led to the exile of Portuguese Jewry, which spread throughout the world. However, throughout the generations, they kept Portuguese as their native language, using it for everyday dealings, in their religious services, for translations of the Bible and in their business. The recently discovered New World, to which many of them have fled, became the Promised Land for some. …

As far as the most recent studies allow us to ascertain, few of the descendants of the Jews who left Portugal between the 15th and 18th centuries came back in the 19th and 20th centuries, although a small number of cases are known. But those who settled here after the abolition of the Inquisition generally came from elsewhere and were not returning….

Beyond the shadows, in almost total anonymity, albeit as outward converts, whole ‘Jewish’ communities have appeared, with their rites, habits and customs, some now corrupted in essence but simply maintained in recent years as part of some resistance related to an idea of faith. This was the origin of Marranismo. The so-called ‘Jews of Belmonte’ are in this category.”[3]

The number of Jews living in Portugal around the turn of the 15th to the 16th century has been estimated at 10% of its 1.5 million inhabitants by Jorge Martins[4] and Paulo Mendes Pinto.[5] Other estimates quoted by this author mention a Jewish population of 30,000 to 60,000 souls towards the end of the fourteenth century, equivalent to 3-6% percent of residing total population. Estanislau Mata Costa mentions between 60 and 70 thousand Jews living in Portugal in the 15th century. (Preface to Maria José Ferro Tavares “As judiarias de Portugal”, CTT, Lisboa, 2010[6])

By the end of the 15th century Carvalho[7] counts at least 134 Jewish communities (judiarias) in Portugal reaching a total population of ‘perhaps’ 100,000 people, or around 10% of total residents in Portugal. Laura Cesana mentions 300 thousand New-Christians by the end of the 15th century.[8] Jorge de Leão, cited by Carvalho, would mention around 60 thousand New-Christians (Cristãos Novos), i.e. force converted Jews, aka baptizados em pé, or baptized standing, by 1542, but only 24-30 thousand by 1605, and only 10 thousand by 1631, according to António Borges Coelho, also quoted by Carvalho.

- S. Révah estimates New-Christians would make around 10 percent of Portuguese total population in the year of1497. (in António José Saraiva “Inquisição e Cristãos-Novos”, Editorial Estampa, 1994, p.216)

Others claimed “In the early 14th century, more than 200,000 Jews lived in Portugal, which would be tantamount to about 20 percent of the total population.”

Alexandre Herculano doubts that in Middle Age Europe laws and rules would have been more favorable to the Hebrews than in Portugal, Jews who would exert a great influence in the kingdom, having exercised “the supreme inspection over the public income” under the reigns of D. Dinis and D. Fernando. (“História da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisição em Portugal”, Publicações Europa-América, 198? (1854-9), first of three volumes, p.57-58)

Afonso Henriques, Portugal’s first king, would already have taken advantage of the Jews as settlers and initiated a policy of trust towards them, namely putting the tax collection under the authority of Yahia Aben-Yaisch.[9]

Figure 87 – Jewish communities in 15th century Portugal

The 1492 eviction edit in Spain, after the implementation of the inquisition there 12 years before, would have through migration caused an increase of the Jewish population in Portugal from 40,000 to 120,000 people.[10] Other estimates are even higher, like the one of Herculano, according to whom around one third of the expelled 800 thousand Jews from Spain would have found refuge in Portugal.[11] In 1493, however, John II of Portugal ordered many 2 to 10 years old Jewish children to be separated from their families and deported to the recently discovered S. Tomé equatorial West-African island.[12]

1496 with the edit of eviction decreed by Manuel I – which by the way also evicted the Muslims, and already in the year of 1515 requested the pope to institute the inquisition[13] – and 1536 with the introduction of the inquisition in Portugal[14] by the pope on request of king John the third,[15] were the most important dates sealing the fate of Jewish people in Portugal for centuries to come.[16]

The inquisition would have been instituted in Portugal, as well as in the other countries ‘benefiting’ from such an institution[17], as a form to defend both the king’s and nobility power, already occupying top ranks of the church hierarchy. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.57) This author quotes estimates of a population of Lisbon around 165 thousand people of which 3189 friars and nuns for the year of 1620. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.58) He also mentions several members of the high nobility, like the Marquês do Alegrete, the Marquês de Marialva, the Visconde de Ponte de Lima and the Conde de Atouguia as “familiares do Santo Ofício” or low ranking inquisition officials/collaborators. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.127)

This author, based on a segmentation of the accused and condemned, describes the inquisition as a tool of the nobility and church, the persecutors, against the bourgeois, or business people, academics, physicians, and menial administrative and handicraft job holders, the persecuted. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.201-216) One could also interpret the inquisition as a wealth redistribution mechanism from the business class to the nobles and clerics. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.257)[18]

Afterall, according to this author ‘business men’ (homens de negócio) would in many instances be considered synonymous of ‘men of the Hebrew nation’ (homens da nação hebraica). (Saraiva, opus cit, p.248) From the 1300 condemned and executed by the Portuguese inquisition, and according to an estimate provided by António Joaquim Moreira for the period 1682-1691, more than 50 percent would belong to the bourgeoisie, 30 % to the handicraft and 12 % to the ‘humble classes’. (in the 1994 edition of Saraiva’s book)

Figure 88 – Jewish communities in 14th century Portugal, from David A. Canelo “Os últimos judeus em Portugal”, Belmonte, 2001, p.76

Till then, particular conditions in Portugal were deemed “very favorable to assimilation” by Saraiva. (opus cit., p.45) This author mentions (opus cit., p.38) the force conversion of all Jewish children less than 14 years old as one of the measures taken around the eviction decree. These children would have been taken away from their families and delivered to Christian families. Their trace would have been lost, even if Saraiva quotes one 18th century writer – D. Luis da Cunha – as stating they would have been raised in the Lisbon surrounding area, and would be the ancestors of those nowadays called ‘saloios’.[19]

However, the biggest traumatizing events took the shape of pogroms in Lisbon 1449 and especially 1506, where thousands (some say 3 thousand, Jorge Martins 2006, vol.1, p.154, or between 2 and 4 thousand[20], being the lower figure the most consensual, Jorge Martins, 2015, p.35) of allegedly Jewish people were massacred by a Lisbon mob instigated by a couple of Catholic monks starting around the northeastern corner of Rossio square. [21]

Other pogroms/massacres of Jews in Portugal would have happened in Lisbon, Évora, and Coimbra in 1385, in Lisbon in 1449, and others between 1482 and 1484. They would, however, only represent a small percentage of similar events in all of Iberia.[22] Portugal and Navarre would have escaped any outbreak of violence in the context of the infamous 1391 riots in Iberia. (Elukin, Jonathan “Living Together, Living Apart: Rethinking Jewish-Christian Relations in the Middle Ages”, Princeton University Press, 2007, p.112)

Estimates of Jewish population residing in Portugal for the year 1604 only count around 6 thousand families, or 30 thousand individuals. (Saraiva opus cit, p.44)

Only the authoritarian actions by the Marquis of Pombal in the last quarter of the 18th century equalizing the status of old and new Christians, while commanding the elimination of lists of New Christians (Cristãos Novos, or force converted Jews) and abolishing death by fire and torture[23] and the extinction of the inquisition by the liberal parliament of 1821 did reverse their condition of a persecuted community.[24]

Jorge Martins (2006, vol.1, p.171) mentions almost half hundred persons/year burnt on the stick from 1540, and a total of 24522 people sentenced by the inquisition courts of Lisbon, Évora and Coimbra between 1536 and 1732.

He quotes Francisco Bethencourt’s estimate of 44817 inquisitorial processes in the four courts of Lisbon – with authority spreading to Brazil, Africa and India (until the inquisition was also established in Goa in the year of 1561, Évora, Coimbra and Goa[25], of which 1865 would have been condemned to the death penalty in Lisbon, Évora and Coimbra between 1536 and 1767.[26] (ibidem, p.183)

Antunes quotes Israel Salvatore Révah, who in Diário de Lisboa would have stated that between 1548 and 1632, and according to inquisition registers, 3565 new-Christians would have been sued in Lisbon alone.[27]

Estimates for the decade between 1682 and 1691 mention 1329 persons penanced and executed, 659 men and 670 women. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.201) All in all, there would be around 40 thousand inquisition processes archived in the Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, mainly originating between the years 1540 and 1760. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.255)

As a curiosity let me refer to the fact mentioned by Meyer Kayserling[28], according to whom many of the surviving members of the Portuguese expedition defeated 1578 in Alcácer-Quibir (Morocco) would have been purchased as slaves by local Jews descending from those who would have been expelled from Portugal some generations before. In general, they would have been fairly treated by their owners, who would have sold many of them on back to Portugal.

According to Avraham Milgrom (“Portugal, Salazar e os Judeus”, Gradiva, 2010, p.21) the last execution of New-Christians (force converted Jews) in an auto-de-fé under the orders of the Portuguese inquisition would have taken place on October 27th, 1765. According to Meyer Kayserling (“História dos Judeus em Portugal”, Pioneira, S. Paulo, 1971 (1867), p.288) the last execution by fire under orders of the inquisition (auto-da-fé) would have taken place on the 19th of October of 1739. Laura Cesana mentions 1765 as the year of the last auto-da-fé,[29] “after two hundred and twenty-five years of persecution which left thousands dead[30] and saw some 40,000 law suits.”

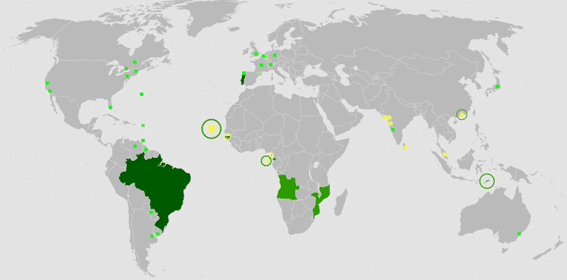

Intense international business activities and mobility between different Sephardic Jewish communities of Portuguese extraction would have developed in the 18th century, namely among those established in Venice, Livorno, Bordeaux, Bayonne, London, Amsterdam and Hamburg, and overseas in Curaçao, Jamaica, Barbados, Charleston, Philadelphia and New York.[31] In many of these places “Portuguese” would be considered tantamount to Jew. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.270-1)

People from the Hebrew nation (“gente da nação hebraica”) as they were called in Portugal turned into people of the Portuguese nation (“gente da nação portuguesa”) while abroad. (Saraiva, opus cit., p.271)

The new synagogues in Lisbon (Shaare-Tikva, or Gates of Hope) and Porto (Kadoorie Mekor Haïm, or Source of Life) were built 1904 and 1929-1938 respectively.[32] In Belmonte a synagogue would have been recently inaugurated,[33] namely the Bet Eliahu synagague in 1996, according to David Augusto Canelo.[34]

The Jews had lived in relative freedom and piece on the Iberian Peninsula for centuries, since the third century, where they were probably transported to on Phoenician ships. The first written vestige – a gravestone showing a menorah[35] – was identified in Mértola, where it is kept in the local museum, and dated from the year 482 AD. (ibidem, p.117)[36] A slightly different version:

“The oldest archaeological remnant, witnessing the presence of Jews in Portugal, is a 6th century ledger, found in Espiche, close to Lagos (Algarve).”[37] Laura Cesana[38] states that “it was believed, until a few years ago, that the most ancient vestiges found were fragments of two tombstones from the VI or VII centuries. They were discovered in the cemetery of Espiche, in the Algarve, near Lagos and are currently in the Carmo Museum in Lisbon.”

Older synagogues were built in 1260, extinct in 1317, and another in 1307, also in Lisbon. (ibidem vol.2, p.171) This author also mentions Jewish cemeteries in different neighborhoods of Lisbon. Further news of synagogues are reported in Tomar, “the only surviving XV century synagogue which was built for that purpose and fully operational for at least 30 years, practically until the time of D. Manuel I’s decree”[39].

Currently open to the public as a museum as promulgated by rightwing dictator Salazar in 1939[40], Castelo de Vide, Guimarães, Porto, Évora, Belmonte (Bet Eliahau, 1996), Bragança (Shaaré Pidyon – Gates of Redemption), Covilhã (Shaaré Cabaah – Gates of Tradition),[41] Ponta Delgada and Monchique.

The Jews would also have been responsible for the introduction of the printing press in Portugal[42] around 1485[43] or 1487[44], and were recruited by the royal houses as financiers and tax collectors, and assumed an important role in many aspects related to the overseas enterprises in both their scientific and financial contributions. (ibidem, p.133)

The financial power of the Portuguese Jewish community reflects on the numerous occasions of crisis the crown has looked for and found barely needed funds, in exchange for clemency, indult, or other rewards, as reported by Saraiva (opus cit. p.273-7) It seems to be factual that the alliance between the crown, the Jesuits and the inquisition, dissolves already in the year 1643 during the D. João IV time in power. (Saraiva, opus cit. p.281)

After the 20th of September 1761, when the last auto-da-fé took place in Lisbon with the execution of the jesuit priest Gabriel Malagrida and the Cavaleiro de Oliveira, the Marquis de Pombal, after having nominated head of the inquisition his own brother, transfers this institution from the papal to royal jurisdiction. (Saraiva, opus cit. p.314-5 and 309)

Portuguese-Jewish immigrants founded the first Jewish community in the New World, in the Brazilian state of Pernambuco, and it was from here, from then Portuguese Brazil, that originated the founders of the first synagogue (Sheret Israel) in the then New Amsterdam settlement, later New York city, (ibidem, p.151 and vol.3, p.43) after Portuguese troops reoccupied Recife (Pernambuco) in 1654, and some others also settled in Philadelphia, Richmond (Virginia), Savannah (Georgia), Charleston (South Carolina), Newport and Baltimore.[45]

In 1654, 23 Portuguese Jews arrived in New Amsterdam (New York) apparently fleeing from the Portuguese inquisition in Brazil and became the first Jewish settlers in the United States. The first Portuguese American is supposed to have been a Sephardic Jew.

Some of the widely known Portuguese/Sephardic Jews and their descendants:

- Abraão ben Samuel Zacuto, or Zacuto Lusitano (aka Diogo Rodrigues), (Salamanca, August 12, 1452, or ca. 1450 – Damascus, probably 1515, 1522, or 1532) was a Sephardi Jewish astronomer, astrologer, mathematician, rabbi and historian who served as Royal Astronomer in the 15th century to King John II of Portugal.

- The crater Zagut on the Moon is named after him. Advisor to kings John II and Manuel I as astronomer and chronicler. Doctor of Christine, queen of Sweden. “He made the first astrolabe in copper (they were previously made of wood), he taught how to calculate latitude without using the sun’s meridian and how to calculate lunar and solar eclipses with greater accuracy.

- These inventions helped Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India and had great importance in the Portuguese and Spanish conquests.”[46] “In 1494 in Leiria, Zacuto published one of the first products of the Hebrew printing presses in Portugal, the Almanach Perpetuum, of which we only have fragments in the Livro da Marinharia (Sailing Book) by André Pires, according to Luís Albuquerque.”

- By the time he came from Spain to Portugal after the expulsion of 1492, “he was already a wellknown mathematician, the first to have put together Tábuas Quadrienais do Sol (Quadrennial Sun Tables) to make navigation easier, which were to be used until some 40 years later, when Pedro Nunes calculated his Sun Tables.” [47]

- Yehuda Abrabanel or Isaac Abravanel (1437 Lisbon – 1508 or 1509 Venice), philosopher and treasurer to the Portuguese court, possessed an encyclopedic knowledge. “He occupied this post until the monarch’s (D. Afonso V) death, when he was accused of conspiring against the heir to the throne and had to flee to Castille. His fortune was confiscated by D. João II.

- While in Toledo, he wrote a series of commentaries on the Old Testament, before going into banking again and being appointed Royal Counsellor.” (Cesana, op cit, p.31)

- Amatus Lusitanus, or João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (1511, Castelo Branco – 1568, Salonika), medical doctor, famous in Italy and Salonika, who discovered the circulation of the blood.

- Baruch Spinoza, (24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677), born Benedito de Espinosa, later Benedict de Spinoza, a Dutch philosopher, whose Spanish family would have been expelled to Portugal. You may wish to explore further on this article by Rui Tavares.

- Benjamin Nathan Cardozo (1870, NYC – 1938, Port Chester, New York), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the USA between 1932 and 1938.

- Benjamin Disraeli,

- Damião de Góis (1502 – 1574)

- David Ricardo (London, 18 April 1772 – Gatcom Park, 11 September 1823), a British political economist.

- Diego Velasquez, painter

- Francisco Sanches (1551 Braga -1623 Toulouse), astronomer, physician, philosopher, and mathematician.

- Garcia de Orta (1501 Castelo de Vide – 1568), botanist and physician, made several voyages to Goa (India), where he died, and founded tropical medicine. “The Inquisition judged Orta after his death, ordering his bones to be disinterred and burned in a public ceremony.” (Cesana opus cit., p. 30)

- Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, first rabi of the Americas, a Portuguese Jew from Amsterdam, who settled around 1638 in Recife while under Dutch rule.

- Jorge Sampaio (1939, Lisbon – Oeiras, 2021), mayor of Lisbon between 1989 and 1996, president of Portugal between 1996 and 2006.

- Kruz Abecassis, Nuno (Faro 1929 — Lisbon 1999), mayor of Lisbon between 1979 and 1989.

- Pedro Nunes (1502 Belmonte– 1578), considered the greatest mathematician of the 16th century.

- Pierre Mendés- France (18 June 1954 – 23 February 1955), prime-minister of France during the fifties.

- Ribeiro Sanches, António Nunes (1699, Penamacor -1783, Paris), physician, went into exile at the age of 27, London, Russia (where he was the physician to the imperial army and treated future empress Catherine for a minor ailment).

- Rodrigo de Castro (David Nehemias)(1546-1628), physician and professor, first to publish a work on genecology and legal medical ethics.[48] Personal physician of the sovereign count of Hesse, of the bishop of Bremen, and of the king of Denmark.[49]

- Zacuto Lusitano (1576 – 1642), great-grandson of Abraão Zacuto, physician and philosopher.

- Samuel Usque (1495/1500 – ?), author of “Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel”, Ferrara, 1553, “This is in the form of an allegory whereby Samuel Usque addresses ‘the exiled from Portugal’.

- In addition to being the first work ever written in the Portuguese language by a Jew, Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel is also one of the first literary records of what had happened in Portugal since the entry of the Jews who had been expelled from Spain in 1492, up to the date of the first Inquisition bull (1531), and the first steps towards exile which the ensuing persecution led to.”[50]

Isabel Monteiro in her bilingual book “Os judeus na região de Viseu, A história. A cultura. Os lugares“, Região de Turismo Dão Lafões, (“The Jews in the Region of Viseu. The history. The culture. The places”, Dão Lafões Tourist Centre), 1997 mentions several Jews from the Iberian Peninsula living in the Netherlands: Spinoza, as son of Portuguese parents; Menasseh Ben Israel or Manuel Dias Soeiro (1604-1657), a diplomat, a grammarian, a commentator of sacred texts, and the founder of the first Jewish-Portuguese typography in Amsterdam; Miguel Barrios, a writer and a poet;

M. Tomás Pinheiro, a philosopher; Rosales, a poet, a physician and a mathematician, a friend of Galilei; António da Fonseca, a physician in Flandres in the year 1620 and the author of a treatise about feverish epidemics. In London, Moisés Cohen de Azevedo is the first halkham of the Portuguese Jewish community; Fernando Mendes is the physician to Catarina de Bragança and King Charles II, Jacob de Castro Sarmento, philosopher and physician, is a member of the Royal Society and writes, among other works, a Treatise about Surgical Operations in 1744.

Jewish physicians escaping persecutions in Portugal would have spread to Turkey, Italy, Holland, England, Belgium, Germany, North of Africa and South America.[51] “It is believed that in the 15th century there were around 500 Jewish physicians in Portugal.”[52]

Figure 89 – Escape routes of sefardite Jews in the 15-18th centuries[53]

According to Meyer Kayserling[54], between 5 and 6 hundred Jewish families, with a rabbi and 3 synagogues would then (1867) live around Lisbon and a lot smaller community in Porto.

For comparison sake let me add that according to sources quoted by Jorge Martins (ibidem vol.2, p.14) the ca. fifty thousand Jews living in France around the end of the 18th century made up .2% of its total population, among them the so-called ‘Portuguese’ community, mostly around Bordeaux and Bayonne, the Ashkenazi, in Alsace/Loraine, the so-called Pope’s Jews of Avignon, and the Jews living in Paris. From a total of around 2 million Jews living in Europe, around half lived in Polen, and around 1/8 in the Austrian empire.

Towards and during WWII several Portuguese diplomats have criticized the persecution of Jews and rendered useful extra services to many members of the threatened Jewish community in several parts of Europe. Among them, Jorge Martins (2015, p.167) mentions Veiga Simões[55], Sampaio Garrido, ambassador in Budapest, Teixeira Branquinho, José Caeiro da Mata, and Aristides de Sousa Mendes[56], the best known among them.

Catholic priest Joaquim Carreira would also been nominated as “Just among Nations” for protecting Jews in Rome during the Second World War.[57] Mendes is credited by some to have issued around 30 thousand visas to Jews, among others, fleeing the nazis in his consulate at Bordeaux and respective agencies.[58] Others stick to a more modest, but still significant number between 10 and 15 thousand.[59]

Carlos Fernandes[60] claims only a few hundred visas would have been sold (and not given away) by Aristides, and that he would not have been persecuted by the Salazar regime and fired from public service without a pension. The dispute beween Carlos Fernendes and heirs, and Aristides’ heirs is reported as been dragging in Portuguese courts.[61]

1996 he has been recognized in Israel as “Just anong Nations” and his name was chosen for a sqare in Jerusalem and a street in Telaviv. Very recently, 2020, the Portuguese parliament has unanimously approved a vote for the transfer of Mendes’ remains to the Pantheon, as a gesture of appreciation for his actions.

Between 1933 and the end of WW2 more than 10 thousand Jews would have travelled through Portugal to the New World on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. (Avraham Milgrom “Portugal, Salazar e os Judeus”, Gradiva, 2010, p.73) In the meantime most of them would be assigned to ‘fixed residence zones’ as Ericeira, Caldas da Rainha, Bussaco, Figueira da Foz and Curia, they could mostly leave only by special police authorization. (idem p.142-8)

From the 4303 Dutch Jews of Portuguese extraction only less than 500 would have survived the Holocaust. Avraham Milgrom (“Portugal, Salazar e os Judeus”, Gradiva, 2010, p.318) blames the Portuguese authorities for at least lack of interest and efforts to assist. Similar blame was extended by this author to the Portuguese authorities in the case of Greece and Turkey.

In the 2001 census only 1773 of the inquired declared to share and practice the Jewish faith, 686 living in the greater Lisbon area, 75 in Belmonte[62], 64 in Porto, 78 in the Algarve (of which 13 lived in Faro), and 9 in the Azores.

That same year 12,014 people would have declared to follow the Islamic religion, but current estimates for Muslims inhabiting Portugal hover around 55 thousand[63].

The population declaring to follow the Jewish faith is apparently on a declining path: 1981 – 5493, 1991 – 3519, and 2001 – 1773, while the Islamic one is on the rise (4335, 9134, and 12014 for those same years). (Jorge Martins, “Breve história dos judeus em Portugal”, Nova Vega, Lisboa, 2015, p.183)

“Today there are about 600 Jews living in Portugal, as well as a Marrano community numbering close to 100 individuals.” Marranos[64] or Crypro-Jews, are those, who steadfastly preserved “their Jewish identity, concealed their faith from both neighbors and the Inquisition.” (Laura Cesana, op. cit., p.20)

Esther Mucznik estimates current Jewish population in Portugal to not exceed 2,000 people. She mentions 4 independent Jewish communities currently in Portugal (in Lisbon, Porto, Belmonte and Faro). [65]

“There is not a consensus on the number of Jews living in Portugal, but Sergio Della Pergola estimates the figure of this ancient community to be around 600. However, according to DNA research around a third to a quarter of all Portuguese people have Jewish ancestry from those who were not able to flee, including the current President of Portugal Marcelo Ribelo de Sousa, who has called for greater recognition of the shared roots of the Portuguese and Jewish peoples.” (Jerusalem Post, December 14, 2017)

Laura Cesana (op. cit. p.18-22) enumerates following festivities and old habits, which would bear vestiges of Jewish ritual celebrations and customs:

- The Bodo, the centerpiece of which is the banquet, common especially in the Beira provinces, but with residual traces in the Minho province, during the feast of St. Bento, and in small villages in Trás-os-Montes, such as St. Sebastian’s Remedy in Couto de Dornelas. “Another feast named ‘Bodo of the Lady of the Greens’ is celebrated every year on the last Sunday of July in Barreiro de Besteiros, near Tondela (Beira province). … Researchers state that the ‘bodo’ is clearly Judaic in origin. This feast is also celebrated in a place named “Our Lady of Ribeira”, situated in turn near a locality named Jueus, a village quoted by Alexandre Herculano as an example of Jewish integration in Portugal.”

- “In Tomar the ‘Feast of the Trays’, judging by its ritual significance and the time of year it is celebrated (autumn), bears close resemblance to the Jewish feast of Sukkot.”

- “In Atalaia (Beira Baixa province) and surrounding villages, the “Feast of the Papas” is celebrated (“papas” being a food made of flour) during which the people give thanks to St. Sabastian. The young men wear the “taled”; a mantle of the purest linen traditionally worn by Jews on certain occasions in the synagogue”.

- “Another vestige is the so-called “Feast of the Grasshoppers” celebrated especially in the Beira provinces to ask God for a good harvest, according to the Judaic tradition of “asking before the event”. This celebration is observed on the Sunday closest to 16 January and the origin is thought to precede the advent of Christianity.”

- “Veneration of the Holy Spirit was particularly observed in places where there were Jewish communities so as to avoid the attention of the Inquisition. Originally, it referred to a feast in Jerusalem.”

- “… in Trás-os-Montes, in the Braganza area, it is customary to cut the ends of certain trees, so that they no longer grow upwards but wider – a direct reference to a verse from Leviticus.”

- “It is also a traditional observance not to eat fermented bread during the Holy Week, but rather bread baked between two tiles.”

- “The ‘alheiras’ are sausages made with poultry rather than pork, which is forbidden to Jews.”

- “In Felgueiras, a municipality of Moncorvo (Trás-os-Montes), circumcision is still customary.”

- “In the Beira provinces, both chicken and turkey are bled after being killed, so that their flesh should become whiter. They are thus obeying Moses’ law not to drink blood, just as they do when they wash their homes thoroughly before Easter.”

- “Among the Judaic practices handed down by ancestors, Adriano Vasco Rodrigues mentions customs which are ethnographically intriguing: he asks whether or not the habit of putting the broom behind the door, in Beira and Trás-os-Montes, ‘to force unwelcome visitors to leave’, is of Jewish origin.”

- “He also mentions the six ears of corn which are left to burn under a terracotta bowl when there is some trial to be faced, such as an exam or a voyage, to bring good luck and ‘enlighten the Lord’.”

- “In the Azores, on the island of Terceira, among the culinary specialties are meat balls and cod prepared Jewish-style and roast lamb for Easter.”

- “Lopes Dias reports that in Escalos de Baixo (Beira Baixa province) mothers must go to church after giving birth, and he wonders whether this is not related to the ancient Jewish custom of purification.”

- “In Castelo de Vide, in the Alto Alentejo province, it is customary to kill a goat at Easter and, according to Jewish tradition, eat it in the fields. The lambs are blessed by the priest on Halleluia Saturday before being sold. Once sold, they are killed and bled. Often, on the doors of houses, a cross is painted with this blood – a remembrance of the flight from Egypt. In the procession on Easter Sunday, the municipal flag is carried flanked by the banners of the Arts and Crafts guild, an interesting detail since most craftsmen were traditionally Jews. Many people kill the lamb on Friday, instead of Saturday, unaware they are following the Jewish tradition of not working on the Sabbath.”

- “Linguistic vestiges are also abundant in the toponomy and in many sayings and words, especially in the Beira provinces. For example: goio (goy), tephe (impure) and mesures. Mesureiro (people who are ceremoniuous), comes from mezuza, which is a roll of paper or parchment fitted into the door frame of Jewish homes containing a written prayer: Jews, upon entering or leaving a house, customarily bow.”

- “Today, in Argozelo (Trás-os-Montes) the expression ‘rope Jew’ (judeu de corda) is still used as an insult, derived from the fact that the congregation at the local church were seated in two areas, divided by a rope, indicating their real faith.”

Before ending her contribution to “Signs of Judaism in Portugal. A Collection of books and prints” published in 1999 by the Portuguese Ministry of Culture, Esther Mucznick recalls on pages 125-6 and in her contribution to “Os Judeus portugueses entre os descobrimentos e a diaspora” published by the Gulbenkian Foundation and the Associação Portuguesa de Estudos Judaicos, in 1994, on pages 221-224 “some of the names which over the previous 150 years have made an important contribution to Portuguese society. In alphabetical order:”

ABECASSIS family – one of its descendants is Kruz Abecassis, former chairman of Lisbon City Council.

AMRAM family – very important in Faro, where they settled in the early 19th century – one of its descendants is Salomão Sequerra Amram, cardiologist and professor of Medicine of the Lisbon Medical Faculty, head of the Cardiology department of Santa Maria Hospital, the biggest of Lisbon, honorary president of the Portuguese Heart Foundation and of the Portuguese Cardiac Association.

AMZALAK family, especially Prof. Moses Bensabat Amzalak, professor of Economics, rector of the Technical University of Lisbon, president of the Lisbon Academy of Science – he was vitally importante in obtaining authorisation for Jewish refugees to escape Nazism through Portugal, and was President of the community for over 50 years.

Mimon Abohbot ANAHORY, who worked for ‘O Século’ newspaper.

Mark ATTIAS, professor of Medicine.

Joshua BENOLIEL, who practically created photographic reporting in Portugal.

Sara BENOLIEL, paediatrician.

Jacob BENSABAT, professor and author of educational books.

Alfredo BENSAÚDE, founder in 1911 of Instituto Superior Técnico (Higher Technical Institute), Lisbon.

Joaquim BENSAÚDE, historian who dedicated all his life to the study of the Discoveries and to the defense of the Portuguese nautical science.

Matilde BENSAÚDE, researcher. (A curious footnote: Jorge Sampaio [President of the Republic] and his brother Daniel [a famous child and adolescent psychologist] are also members of the Bensaúde family, as their grandmother was Sara Bensliman Bensaúde).

José ESAGUY, poet and historian, author of several studies on the Portuguese presence in Morocco.

Simy Toledano ESAGUY, writer, painter and composer.

Kurt JACOBSON, chemist, Vice-rector of the University of Lisbon.

Fortunato LEVY, doctor, clinical director of the Jewish Hospital.

Moisés RUAH, doctor.

Samuel Allenby Bentes RUAH, physician, head of the Otorhinolaryngology department of the Hospitais Civis de Lisboa.

Joshua Gabriel Benoliel RUAH, surgeon, chairman of the Board of the Jewish Community from 1978 to 1992.

Semtob Dreiblatt SEQUERRA, lawyer, writer and founder of one of the synagogues in Faro.

“In conclusion, I would say that the main characteristics of Judaism in Portugal today is not the division between Sephardim and Ashkenazim (as it is in so many other countries), but rather the division between a Jewish community which has been in Portugal for little more than 150 years and a remnant of marrano Jewry whose origins go back to the 1500s.” (p.126)

Most recently a skandal arose regarding the certificates of connection to Portugal for Sephardic Jews around the worls applying for Portuguese citizenship benefiting from an exceptional but without time limit law. The Jewish communities of Porto and Lisbon were entitled to issue such certificates and mostly the Porto one would allegedly have abused such authority and suspect connections to politicians, lawyers were laid bare by the press. 12 israeli international footballers and more than 40 in total would already have benefited from this law.[66] Roman Abramovich would also have become a Portuguese citizen since April 2021.[67]

[1] “Fontes remotas da cultura portuguesa” and “Origens orientais da religião popular portuguesa”, both published by Assírio & Alvim, Lisbon, 1989 and 1988, respectively.

[2] Many Portuguese words starting with Al would wrongly be assumed of Arab origin. They could also, according to Moisés Espírito Santo be traced to Chaldean or Hebrew origins. (1988, p.258)

[3] “Signs of Judaism in Portugal. A collection of books, and prints”, Ministry of Culture, Lisbon, 1999, p.11-21

[4] “Os portugueses e os judeus”, volume I-III, Nova Vega, 2006

[5] “Portugal: uma terra mítica para os judeus?” in Miguel Sanches de Baêna and Paulo Alexandre Loução (coord.) “Grandes enigmas da história de Portugal”, Ésquilo, vol.1, p.89-97

[6] This work describes with some detail the main Jewish communities she could trace.

[7] António Carlos Carvalho “Os judeus do desterro de Portugal”, Quetzal, 1999, p.11

[8] “Vestígios hebraicos em Portugal – viagem duma pintora. Jewish vestiges in Portugal – travels of a painter”, published by the author, 1998 (1997), p.18

[9] David Augusto Canelo “Os últimos criptojudeus em Portugal”, Cãmara Municipal de Belmonte, 2001 (1987), p.25

[10] António José Saraiva (“Inquisição e Cristãos Novos”, Editorial Inova, Porto, 1969, p.37) quotes two almost contemporary authors mentioning 120 thousand people and/or 20 thousand families.

[11] “História da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisição em Portugal”, Publicações Europa-América, 198? (1854-9) (3 vol.), first volume, p.68.

[12] Laura Cesana “Vestígios hebraicos em Portugal – viagem duma pintora. Jewish vestiges in Portugal – travels of a painter”, published by the author, 1998 (1997), p.17

[13] Alexandre Herculano “História da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisição em Portugal”, Publicações Europa-América, 198? (1854-9) (3 vol.), first volume, p.93

[14] Was 1821 extinguished by unanimous vote of the recently elected liberal national parliament. (Jorge Martins 2015, p.111)

[15] On the multiple and extensive shenanigans between the papal and royal courts inherent to the creation and implementation of the inquisition in Portugal you may read Alexandre Herculano’s “História da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisição em Portugal”, Publicações Europa-América, 198? (1854-9) (3 vol.), where the Jews are described as “endowed with good and bad qualities to a high degree”, and “set apart by the invincible pertinacity, by the craving for gain, taken to sordidness, by the shrewdness, and by the love for work.” (opus cit p.41) (my literal translation.)

[16] “England expelled its Jews in 1290, and France’s final expulsion of the Jews occurred in the late fourteenth century.” (Elukin, Jonathan “Living Together, Living Apart: Rethinking Jewish-Christian Relations in the Middle Ages”, Princeton University Press, 2007, p.116) “After Jews were expelled from the royal domain in 1182, for example, they must have felt confident enough about their place in French society to return in 1198.” (ibidem, p.86) Louis XIII would also have ordered the expulsion of all Jews from France in 1615, and Charles V in 1550, even if never implemented, according to Carvalho (ibidem, p.48 and 101) Winder (2013) dedicates his whole third chapter to the “Expulsion of the Jews” from the UK in 1290.

[17] For a thorough description of the inquisition’s activities in mentioned countries you may refer to “História das inquisições. Portugal, Espanha e Itália”, by Francisco Bethencourt, Círculo de Leitores, 1994

[18] This point of view is strongly contradicted by the French hispanist Israel Salvator Révah is a series of contributions included in the 1994 edition of Saraiva’s book by Editorial Estampa.

[19] Orlando Ribeiro (“A formação de Portugal”, Ministério da Educação. Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa, Lisboa, 1987, p.40) identifies an Arabic origin to this word meaning rural inhabitant of the Lisbon surroundings.

[20] Also according to Meyer Kayserling “História dos Judeus em Portugal”, Pioneira, S. Paulo, 1971 (1867), p.131

[21] In retaliation the king ordered the execution of ca. 50 mobsters, including the two inciting monks. (Jorge Martins, “Breve história dos judeus em Portugal”, Nova Vega, Lisboa, 2015, p.35)

[22] Jorge Martins, 2015, p.23

[23] According to Meyer Kayserling “História dos Judeus em Portugal”, Pioneira, S. Paulo, 1971 (1867), p.288

[24] According to Avraham Milgrom (“Portugal, Salazar e os Judeus”, Gradiva, 2010, p.33) the Marquis de Pombal would already have abolished the inquisition in the 18th century.

[25] Sources mention between 850 and 76 executions by the Goa inquisition from 1660 to 1773. (José Pequito Rebello “Portugal e a Índia”, Lisboa, 1962, p.81-85)

[26] Porto, Lamego and Tomar would also have been sits of inquisition courts. (Alexandre Herculano “História da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisição em Portugal”, Publicações Europa-América, 198? (1854-9) (3 vol.), third volume, p.13.

[27] Antunes, José Freire (dir.) “Judeus em Portugal. O testemunho de 50 homens e mulheres”, Edeline, Versailles, 2002, p.153

[28] “História dos Judeus em Portugal”, Pioneira, S. Paulo, 1971 (1867), p.219

[29] “Vestígios hebraicos em Portugal – viagem duma pintora. Jewish vestiges in Portugal – travels of a painter”, published by the author, 1998 (1997), p.18

[30] “According to José Hermano Saraiva, 1,379 people were burned at the stake up to 1682, after which the killings diminished.

[31] Samuel, Edgar “Relações Internacionais” in Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos & José Sommer Ribeiro (coord.) “Os judeus portugueses entre os descobrimentos e a diáspora” Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1994, p.154. For a thorough description of Portuguese-Jewish communities in the diaspora please refer to António Carlos Carvalho “Os judeus do desterro de Portugal”, Quetzal, 1999.

[32] Graça Fonseca & Costa Bachman “A arquitectura das sinagogas” in Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos & José Sommer Ribeiro (coord.) “Os judeus portugueses entre os descobrimentos e a diáspora” Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1994, p.44-5

[33] Jorge Martins “Breve história dos judeus em Portugal”, Vega, 2015, p. 151. In 1996 according to the testimony of Elias Nunes in Antunes, José Freire (dir.) “Judeus em Portugal. O testemunho de 50 homens e mulheres”, Edeline, Versailles, 2002, p.203. The Jewish community of Belmonte was specifically scrutinized by Jorge Martins especially in its dealing by the inquisition in his recently published book “O judaísmo em Belmonte no tempo da inquisição”, Âncora, 2016.

[34] David Augusto Canelo “Os últimos criptojudeus em Portugal”, Câmara Municipal de Belmonte, 2001 (1987), p.188

[35] Cabral, Maria Luisa (coord.), Pinto, Maria Filomena Silva & Maria Armanda Boavida Couto (org.) “Signs of Judaism in Portugal. A collection of books, and prints”, Ministério da Cultura, Lisboa, 1999, p.11

[36] Several Jewish coins dating back to the first century after Christ would also have been found in the Mértola area. (Jorge Martins “Breve história dos judeus em Portugal”, Vega, Lisboa, 2015, p.10)

[37] Ruah, Samuel B. & Carlos B. Ruah “The maritime discoveries, the Jewish physicians and the diaspora” in Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos & José Sommer Ribeiro (coord.) “Os judeus portugueses entre os descobrimentos e a diáspora” Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1994, p.299

[38] “Vestígios hebraicos em Portugal – viagem duma pintora. Jewish vestiges in Portugal – travels of a painter”, published by the author, 1998 (1997)

[39] Cesana, opus cit., p.43., whose note goes on: “We know it was used as a common jail at the beginning of the XVII century. … In 1600 it became a Catholic chapel, then a hay loft, a wine-cellar and finally , a grocery shop. The building was declared a national monumento on 29 July 1921 and was then bought in 1923 by Samuel Schwarz, who restored it as a synagogue. The eminente researcher donated the building to the Portuguese state in 1939, with the express condition that it become a Luso-Hebraic Museum to house an epigraphic collection with a section dedicated to illustrating the history of Jewish culture in Portugal.”

[40] Antunes, José Freire (dir.) “Judeus em Portugal. O testemunho de 50 homens e mulheres”, Edeline, Versailles, 2002, p. 45

[41] David Augusto Canelo, opus cit.p. 169-170

[42] “The first book printed in Portugal was a Pentateuch, from the shop of Samuel Gacon in Faro in 1487. Shortly thereafter, the Jew of Spanish origin Abraham Zacuto, Portuguese Court Astronomer, published his Almanach Perpetuum, the first of its kind.” José Hermano Saraiva mentions in his “História de Portugal”, 1993, p.156, another ‘first’ in Chaves 1489.

[43] According to Meyer Kayserling “História dos Judeus em Portugal”, Pioneira, S. Paulo, 1971 (1867), p.78

[44] Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos & José Sommer Ribeiro (coord.) “Os judeus portugueses entre os descobrimentos e a diáspora” Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1994, p.47

[45] António Carlos Carvalho (“Os judeus do desterro de Portugal”, Quetzal, 1999, p.164) also reminds us that the poem included in the socket of the statue of liberty “Give me your tired, your poor, your heddled masses…” was authored by Emma Lazarus, a sephardic Jew.

[46] Cesana, op cit, p.30.

[47] Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos in “Signs of Judaism in Portugal. A collection of books, and prints”, Ministry of Culture, Lisbon, 1999, p.29-30

[48] Ruah, Samuel B. & Carlos B. Ruah “The maritime discoveries, the Jewish physicians and the diaspora” in Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos & José Sommer Ribeiro (coord.) “Os judeus portugueses entre os descobrimentos e a diáspora” Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1994, p.302

[49] Carvalho (ibidem, p.107).

[50] Lúcia Liba Mucznik “Os Judeus …”, p.118

[51] Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos & José Sommer Ribeiro (coord.) “Os judeus portugueses entre os descobrimentos e a diáspora” Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1994, p.302

[52] Ruah, Samuel B. & Carlos B. Ruah “The maritime discoveries, the Jewish physicians and the diaspora” in Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos & José Sommer Ribeiro (coord.) “Os judeus portugueses entre os descobrimentos e a diáspora” Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1994, p.301

[53] Reproduced from Paulo Curado “Judeus sefarditas. Reparação histórica em Espanha marcada por processos fraudulentos” in Público, Feb.11, 2022

[54] “História dos Judeus em Portugal”, Pioneira, S. Paulo, 1971 (1867), p.292

[55] About this diplomat you may care to read Diogo Ramada Curto “O Desconhecido Veiga Simões”, A Revista do Expresso, 28 Outubro 2017

[56] According to Avraham Milgram (“Portugal, Salazar e os Judeus”, Gradiva, 2010) Aristides would have issued 2862 visas between the first of January and June the 22nd of 1940 as consul in Bordeaux. Many others would have been issued by him at the consular sections of Bayonne and Hendaye on his way to Portugal after he had been summoned back for disobedience. According to Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos he would have saved “around 30,000 people” (Introduction to Cabral, Maria Luisa (coord.), “Signs of Judaism in Portugal. A collection of books, and prints”, Ministério da Cultura, Lisboa, 1999, p.21.) On the activities of this consul you may also see “Aristides de Sousa Mendes – Um Herói Português” by José-Alain Fralon, Presença, 1999.

[57] Sofia Lorena “Padre Joaquim Carreira vai ser “Justo entre as Nações” por salvar judeus em Roma”

in Público Dec.11, 2014

[58] Irene Flunser Pimentel “A versão falseada sobre Aristides Sousa Mendes na Wikipedia”, in Público, June 21, 2020.

[59] Margarida Magalhães Ramalho “Elogio da desobediência”, in A Revista do Expresso, 2490, July 18, 2020

[60] “O cônsul Aristides de Sousa Mendes, a Verdade e a Mentira”, Grupo de amigos do autor, Lisboa, 2013

[62] Laura Cesana (opus cit, p.38) states that “the present community has 160 members.”

[63] Against around 2 thousand Jews, as estimated in “Cosmovisões religiosas e espirituais. Guia didático de tradições presentes em Portugal” Alto Comissariado para as migrações, Lisboa, 2016

[64] Marranos, or swine in Spanish, “as the New Christians were popularly if inelegantly termed.” (Boxer 1948, p.144)

[65] Esther Mucznik “Uma Europa sem judeus” in Público, January 21, 2022

[66] Paulo Curado “Há 12 futebolistas internacionais por Israel que são portugueses”, in Público, October 15, 2022

[67] Paulo Curado “Roman Abramovich é cidadão português desde Abril”, in Público, December 18, 2021