The Euro / Debt Problem

Rodrigues (2012) and Azevedo (1988) count till now several episodes of default or debt renegotiation by the Portuguese state along its existence in following years: 1543-4, 1549 and 1560 (trade factory of Antwerp, and Casa da Índia in Lisbon), 1605 (during the personal union with the Spanish crown), 1828 (shortly after Brazil’s independence and during the civil war between absolutists and liberals – in the European sense of the word), 1837, 1841, 1846, 1850 and 1892 (a few years before Portugal became a republic and one of the causes of it).

Alexandre Herculano mentions estimates of public debt extraordinary high levels and respective interest payments and rates for the sixteenth century.[1]

Near defaults implying a bailout by outside powers happened recently in 1978, 1983, and 2011. Far from being unique the 2011 crisis can be considered one more in a long line of similar events, this time aggravated by the international subprime recession and subsequent euro related bailouts of Greece, Ireland, Cyprus, and Spain’s banks.[2]

Democracy has not been especially compatible with sound debt management in Portugal over the centuries.

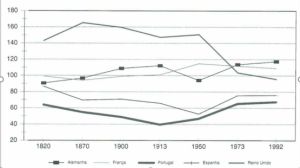

In the 45 years leading towards the end of the 20th century, and coincidentally the Euro implementation, the Portuguese economy was the fastest growing in Europe, even if after a miserable 19th and first decades of the 20th century.[3]

Figure 1 – GDP per capita – European Union = 100, from Abel Mateus, 1998, p.25

The 2011 lack of access to international financial markets by Portugal can of course be linked to the 2007-9 international financial turmoil triggered by the subprime crisis in the USA, but also to the adoption of the Euro by Portugal since its inception 1999-2002.

Not so important but nevertheless significant in this context should also be mentioned China’s admission to the WTO, and the Eastern European countries admission into the EU between 2004 and 2013 (in 2004 the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, and the Slovak Republic; in 2007 Bulgaria, Romania; and in 2013 Croatia). Both China and Eastern Europe can be seen as potential competitors with Portuguese manufacturing industry and East European countries with Portugal’s claim on EU funds.

At the micro level, namely the use (and abuse) of these EU funds in different shapes and forms seems not to impact very positively (if at all) the performance of subsidized firms, as a recent paper by Fernando Alexandre seems to illustrate.

Figure 120 – What happens to firms 3 years after they obtain the European incentive?

Let’s go back to the Euro, though. Perhaps the most important of these circumstances have been disregarded by Portuguese negotiators and economists. The Euro can be seen as a step back from comparative advantage, according to which even the overall least productive country would have a way to compete internationally through foreign exchange devaluation, to the absolute advantage paradigm, according to wich only products/services that enjoy higher productivity would be able to compete internationally. It was the combination of these circumstances that can be held responsible for the poor performance of the Portuguese economy over the previous twenty years.

Ricardo Cabral and Ricardo Sousa (2019)[4] draw a negative balance of the first 20 years of the Euro, perhaps not so much for Germany and Holland but certainly for Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain, the so-called PIGS.

Much of this unbalanced impact can probably be attributed to the fact that the architecture of the euro has been incomplete and imperfect from the start and more than twenty years later would not have been satisfactorily corrected and completed with a budgetary union, without which government bond markets would persist very fragile.

Eurobonds, i.e. commonly issued debt, common budget of at least 10-20 % of GDP, instead of the current 1 % or a little more, and fiscal transfers would very probably also help on the way of a better monetary and political union[5], and in this context one may envision the effects of the current Corona Virus pandemic as moving the EU in the right direction, even if many snags still prevail, like the famous rebates and veto rights for individual ‘frugal’ members.

Figure 121 – GDP per capita as a percentage of German GDP[6]

In the absence of the power for devaluing the currency and of a budget union allowing for transfers from advantaged to disadvantaged EU member countries, that was basically the reason for the devaluation of labour costs/prices imposed by the international troika of lenders during the so-called assistance program to the Portuguese economy from 2011 to 2014-15.

Figure 122 – Portugal among the least growing Euro countries (Expresso April 9, 2021)

Post hoc ergo propter hoc may apply in this context and not be disavowed as a fallacy by the facts and available theories. One is at odds to find a different and better explanation for the slow growth of the Portuguese economy in the last 20 years or so. The only alternative or complementary explanation that comes to mind being the 2001 joining of China to the WTO (World Trade Organization). Some of the Portuguese exports to the EU (European Union) and third countries – mostly textiles and similar low labor cost products – may have been jeopardized by careless or powerless negotiators.[7]

As an ancillary reason for the Portuguese economy’s poor performance in the last 20 or so years, one could also add the 2004 EU enlargement to the East. Then, several East European countries joined the EU, and 16 years later half of them have surpassed Portugal’s GDP per capita.

Figure 123 – Ratio of per capita Portuguese GDP over European average

However, arrived here, I don’t believe the EMU/Euro should be disbanded, like some seem even recently to suggest[8], and that Portugal should leave the Euro[9], now that most of the detrimental consequences have been absorbed by its economy and that the Portexit’s costs would be huge. Mutatis mutandis that’s apparentlywhat applies to other South European less competitive countries like Italy. [10]

Look forward instead, and complete and correct the monetary union’s shortcomings like the lack of a quantitatively significant common budget with redistributional competences, despite the always prevalent moral hazard obsession.

[1] “História da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisição em Portugal”, Publicações Europa-América, 198? (1854-9) (3 vol.), third volume, p.24)

[2] Pedro Braz Teixeira “O euro e o crescimento económico” FFMS, 2017

[3] Abel Mateus “Economia Portuguesa. Crescimento no contexto internacional (1910-1998)”, Editorial Verbo, Lisboa, 1998, back cover.

[4] “20 anos do euro. O problema das lentes a ‘preto e zero’ ”, Público, October 23, 2019

[5] Here we follow grosso modo Paul de Grauwe “Economics of Monetary Union”, Oxford University Press, 2016 (11th edition)

[6] From Ricardo Cabral & Ricardo Sousa “20 anos do euro. O problema das lentes a ‘preto e zero’ ”, Público, October 23, 2019

[7] Carmen Amado Mendes “O impacto para Portugal da adesão da China à OMC” in Zoom, Revista do Centro de Estudos do Curso de Relações Internacionais, nº 14, 2006, p.45-49

[8] Gyorgy Matolcsy “It is time to recognise that the euro was a mistake”, Financial Times November 3, 2019

[9] João Ferreira do Amaral “Porque devemos sair do euro: o divórcio necessário para tirar Portugal da crise”, Lua de Papel, Alfragide, 2013

[10] Alessandro Speciale & Chiara Albanese “Is the Euro to blame for Italy’s woes?” in Bloomberg Businessweek, December 24, 2018