The Inheritance/legacy of the Moors/Arabs/Muslims

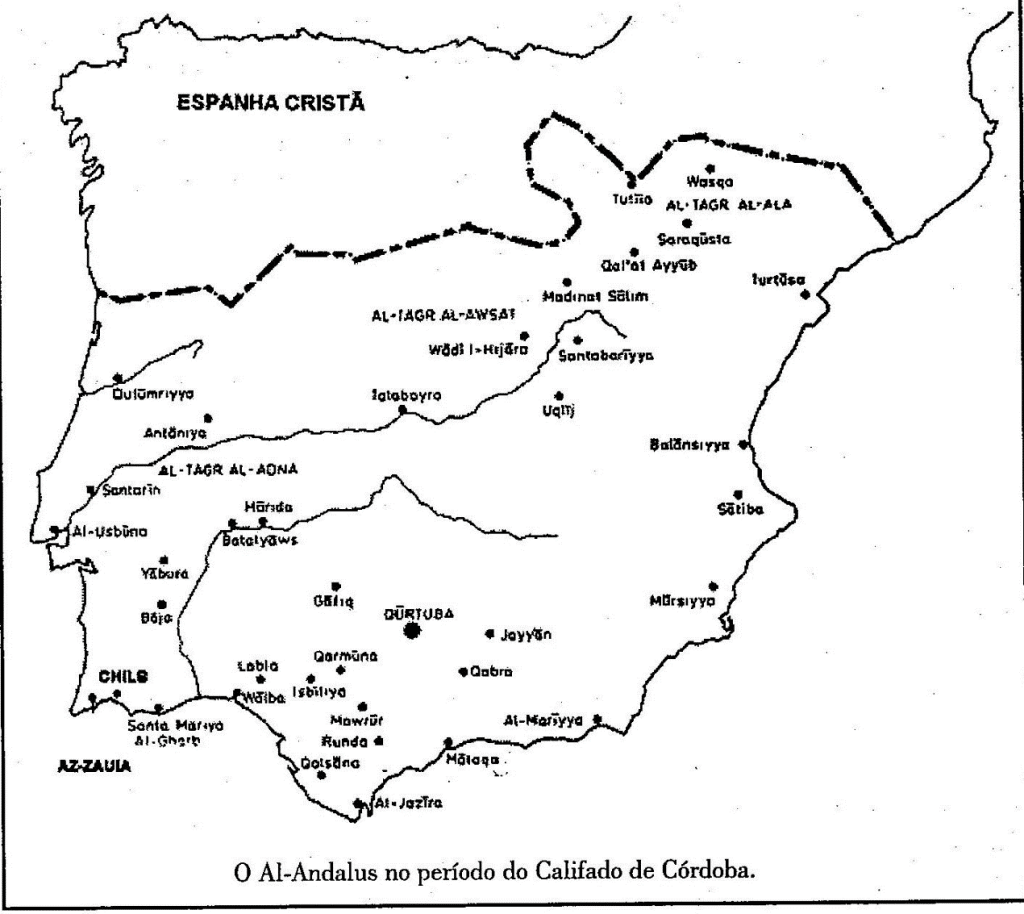

The Muslims/Moors were on the Iberian Peninsula from 710 (Ossónoba/Algarve was taken by Mûsa Ibn Nusayr in 713) to 1492 (coincidentally the year of the first Columbus expedition), when Granada, the last bastion of El Andalus, was conquered by the Castilian Catholic kings.

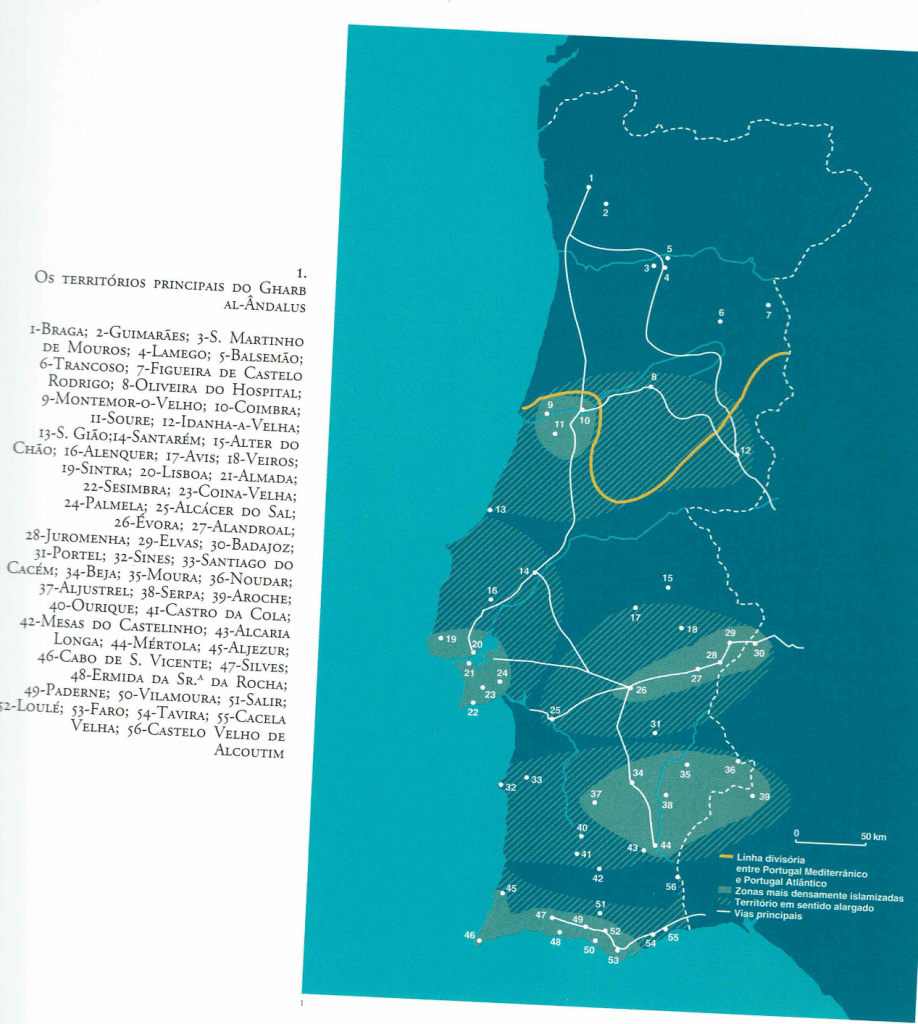

Their control of the Gharb-Al Andaluz in today’s extreme southern Portugal had ended already more than 200 years before in 1250, when Aljezur their last bastion in the Algarve was abandoned. So, the Muslim presence in today’s Portugal encompassed more than 5 centuries.[i] In geographic terms its influence extended from Silves, and Faro in the South to Guimarães and Braga in the North[ii], where it remained a lot more tenuous.

[i] It had taken the Moors only 5-6 years to conquer almost all of the Iberian Peninsula. In contrast it has taken the Christians 5-7centuries to get rid of the Moors there.

[ii] According to Orlando Ribeiro (Portugal. O Mediterrâneo e o Atlântico”, Sá da Costa, 1987, p.57) however, no material witness of Moorish presence and only a few localities’ names would suggest an Arabic origin North of the Douro river.

This is perhaps one more reason why their presence didn’t leave so much built vestiges behind as in the South of Spain. The Gharb was always more peripheric than Granada, and even Seville.

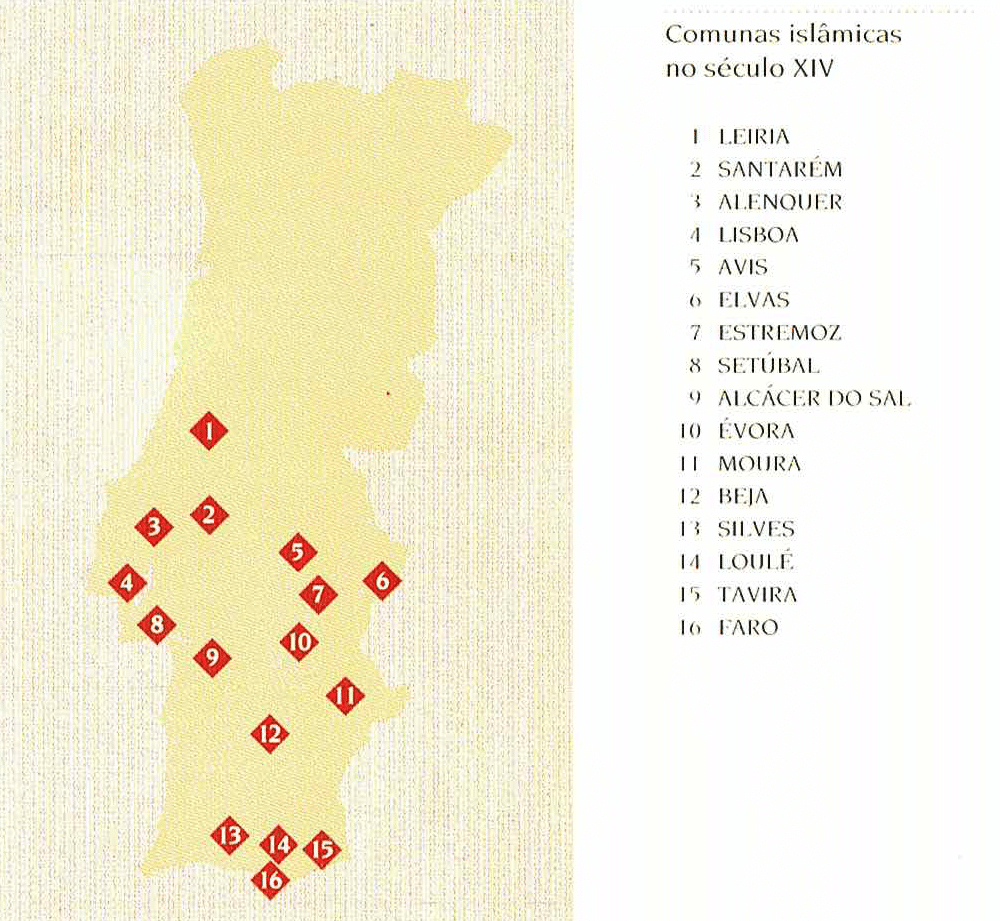

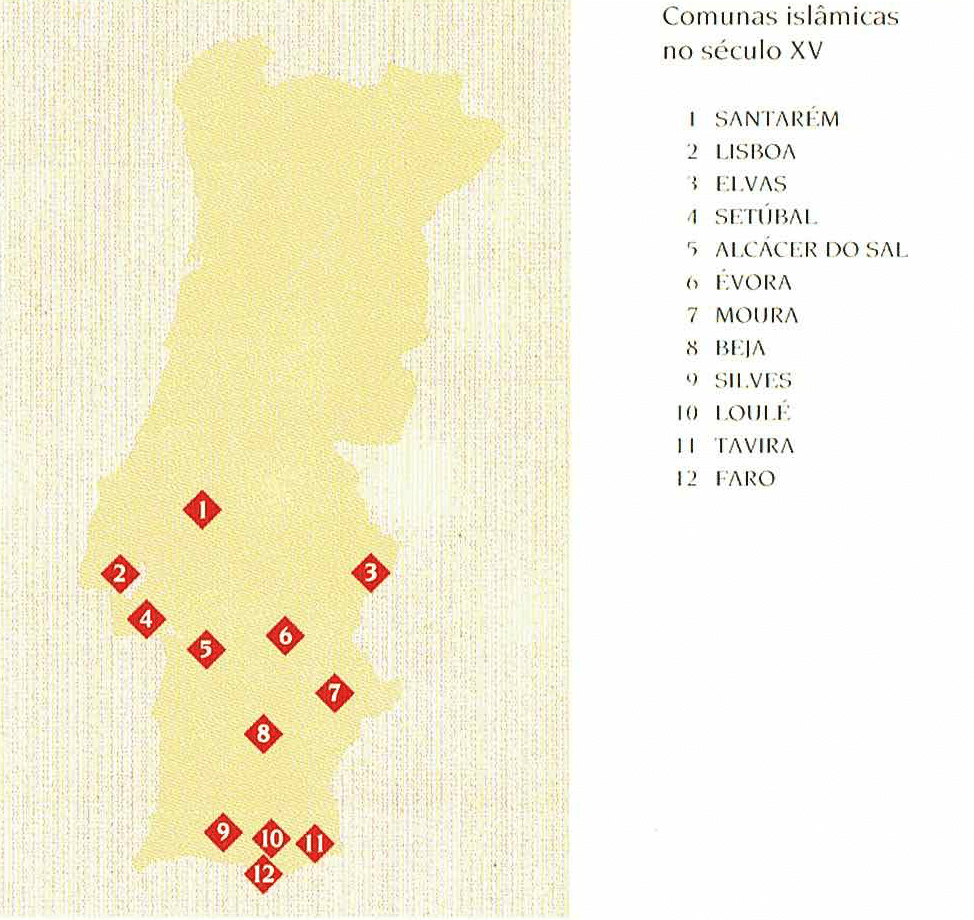

However, the presence of Muslim communities in Portugal continued till the 1496 edict of eviction by King Manuel, which by the way also applied to the Jewish community.

Farming and handicraft would have been the main activities of these communities, perhaps with some national and ‘international’ trade as a complement for a restricted elite group. (Barros p.87-92) Tapestry played a major role among the artisanal activities and came with a elite status for respective job holders.[i]

It was most probably the Arabs that taught the Iberians the main rudiments of sailing, legated them the compass, and probably also the vertical rudder.[ii]

As for population numbers, Barros (p.144), following other authors, estimates that only a total of a little more than 500 Muslims would inhabit the Mouraria (Moorish quarter) of Lisbon, and I would guess that only a few thousand would be living in all of Portugal by the end of the 15th century.[iii]

[i] Perhaps the Arroiolos tapestry of today is a vestige of that.

[ii] António Borges Coelho “Raízes da expansão portuguesa”, Prelo, Lisboa, 1976 (1964)

[iii] Current estimates for Muslims living in Portugal hover around 55 thousand. (“Cosmovisões religiosas e espirituais. Guia didático de tradições presentes em Portugal” Alto Comissariado para as migrações, Lisboa, 2016)

Meca is also the name of a locality in Portugal (around one hour North of Lisbon by car), and many others are from Arab/Moorish origin, like many of those whose designation starts with ‘Al’ (Alcacer, Alcobaça, Alenquer, Algarve, etc.). Alcohol, an English and Portuguese word (álcool), as you suspect by now, is derived from the Arabic too. As is alembic (alembique) from the Arabic al-embik.

Atalaia and rebate are allegedly also two other cases in point. Perhaps Al-qaeda is not far from being at the origin of the Portuguese alcaide, meaning mayor up to the late middle age, and in Spain – in the form of alcalde – up to now, before it unfortunately became familiar for the known reasons.

The current mayor of Lisbon name goes as Fernando Medina, and Almedina is a known publishing company based in the town of Coimbra, where an arch of Almedina is part of the old city wall. Sherif is also a known word in Portuguese, and oxalá is commonly used as a derivation of the Arabic. Let us also not forget that the widely visited Catholic shrine and pilgrimage site bears the same name as the daughter of the prophet, namely Fátima.

Adalberto Alves (“A herança árabe em Portugal”, CTT Correios de Portugal, 2001, p.137) lists around 180 Portuguese words derived from the Arabic, and believes that between 2 and 3 thousand Portuguese words derive from it (ibidem p.78).

Whole dictionnaries were produced on the subject of Portuguese words originating in Arabic, like “Dicionário de arabismos da língua portuguesa”, 2013, by Adalberto Alves, “Influência arábica no vocabulário português”, 1958/1961, 2 volumes by José Pedro Machado, and “Vestigios da Lingoa Arabica em Portugal”, 1830, by Fr. João de Sousa and Fr. Joze de Santo Antonio Moura. The whole of the first volume of the one by Machado is dedicated to words starting with an a, which gets reflected in the fact that in the Portuguese language words starting this way represent such an over proportional part of its dictionaries.[i]

Music instruments like the adufe[ii], alaúde. gaita, tambor, rebeca, guitarra, rebabe, pandeiro, and the atabale would also have an Arabic etymology. According to this same author, the Fado (from the Arabic khadû?), the Cante Alentejano (from the sulâmiyya type of Sufi song style?), and other types of Portuguese folk music could also be traced back to some Arabic origin. (Alves, 2001, p.87)[iii]

[i] Unfortunately, and according to information provided by Fabrizio Boscaglia, there is currently no available Arabic-Portuguese language dictionary, besides the two previously mentioned for Portuguese words with Arabic origin: Adalberto Alves “Dicionário de arabismos da língua portuguesa”INCM, Lisboa, 2013 and José Pedro Machado “Influência arábica no vocabulário português”, 2 volumes, Edição de Álvaro Pinto, Lisboa, 1958 and 1961.

[ii] Unfortunately, and according to information provided by Fabrizio Boscaglia, there is currently no available Arabic-Portuguese language dictionary, besides the two previously mentioned for Portuguese words with Arabic origin: Adalberto Alves “Dicionário de arabismos da língua portuguesa”INCM, Lisboa, 2013 and José Pedro Machado “Influência arábica no vocabulário português”, 2 volumes, Edição de Álvaro Pinto, Lisboa, 1958 and 1961.

[iii] Adalberto Alves dedicated a whole book to the connections between Portugal and Arabic music: “Arabesco. Da música árabe e da música portuguesa”, Assírio & Alvim, Lisboa, 1989.

Cláudio Torres & Santiago Macias (“O legado islâmico em Portugal”, Círculo de Leitores, 1998, p.33) call our attention to the fact that, as the Jews also did, trade was welcome and not something sinful and hurtful in the Islamic society, as it was by then overwhelmingly considered by feudal Christianity. The only old mosque building still standing in Portugal is the one in Mértola, even if transformed into a Catholic church some centuries ago. Many old Catholic churches were built on sites previously occupied by mosques like the old Lisbon cathedral.

Reflecting the longer Muslim presence in the South of Portugal, more words used here show an Arabic origin than in the North. Orlando Ribeiro (Portugal. O Mediterrâneo e o Atlântico”, Sá da Costa, 1987, p.57) gives us following examples from a list with more than one hundred cases.

José Mattoso[i] lists following Portuguese substantives as having an Arabic origin:

Related to construction: alicerce (foundation); related to metallurgy: almotolia, argola, aldraba, alfageme; related to rawmaterials: âmbar, açafrão, aljôfar, almagre, azougue; related to weights and measurements: almude, alqueire, arrátel, arroba, cafiz , fanega, folforinho, maquia, quintal, teiga; related to urban network: arrabalde, azinhaga, chafariz, alcáçova, almedina, almuinha; related to food: adiafa, acepipe, açorda, açúcar, almôndega, açafrão, acelga, azeite; medicinal plants, horticultural products and flowers: açucena, alcachofra, alecrim, alface, alfarroba, alfazema, algodão, azambuja, laranja, limão; related with irrigation and milling technology: acéquia, açude, alcatruz, azenha, nora, atafona; related to manufactures and supply activities: alfândega, armazém, azémola, récua, almocreve, azemel, açougue. But of course many more can be identified in the two dictionaries mentioned in note 7.[ii]

[i] “Identificação de um país. Ensaio sobre as origens de Portugal, 1096-1325”, first volume, Editorial Estampa, Lisboa, 1988 (1985), p.326

[ii] A lot more details can be traced in “O Islão em Portugal” by Claudio Torres and Luis Leiria, CD-Rom, Creatix, 2006

See more: Arabs