Preface

Preliminary thoughts

“Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.” Samuel Johnson, April 7, 1775

“…[T]he Portuguese expansion of the 15th century constitutes an entirely new event in the History of the world.” Orlando Ribeiro, “Originality of the Portuguese Expansion”[i]

[i] Synopsis of “Originalidade da Expansão Portuguesa”, Edições João Sá da Costa, Lisboa, 1994, p.155 – written between 1954 and 1960

On the fourth of July 2007 three men met in Lisbon, Portugal, representing the European Union, Portugal and Brazil. All of them spoke the same native language, Portuguese, the sixth language with more native speakers in the world – over 200 million, and the first in the Southern hemisphere.

President Lula da Silva from Brazil, a former union leader and labourer, prime minister José Sócrates from Portugal, the country which held the EU presidency for that semester, and EU Commission president José Manuel Barroso came together in a summit supposed to strengthen the links between the EU and Brazil in a rare display of vitality that the Portuguese influence in the world didn’t show for quite a few centuries perhaps.

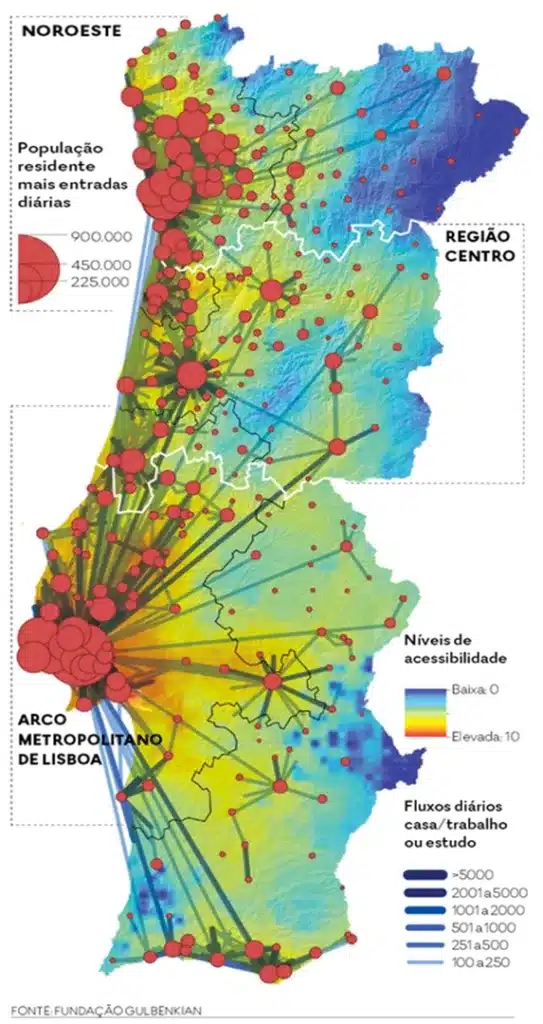

Was this a signal of newly won predominance, or a last hiccup in a long decadence from first and only European nation state[i], then a world empire, to a marginal role in world affairs, and an extremely unbalanced domestic economic geography?

“The first stage of the overseas expansion of Europe can be regarded as beginning with the capture of Ceuta by the Portuguese in 1415 and culminating in the circumnavigation of the world by the Spanish ship Victoria in 1519-22. [Last remain of the fleet which set sail from Spain under the command of the Portuguese renegade Ferdinand Magellan, or Fernão de Magalhães] The Portuguese and Spaniards had their precursors in the conquest of the Atlantic Ocean, but the efforts of these adventurers had not changed the course of world history.

Vikings had voyaged to North America in the early Middle Ages, but the last of their isolated settlements on Greenland had succumbed to the rigours of the weather and the attacks of the Eskimo before the end of the fifteenth century. Italian and Catalan galleys from the Mediterranean had boldly ventured into the Atlantic on voyages of discovery in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries: but what they sought is uncertain, and what they found is equally obscure, though they may have sighted the Açores.” (Boxer 1961, p.5)[ii]

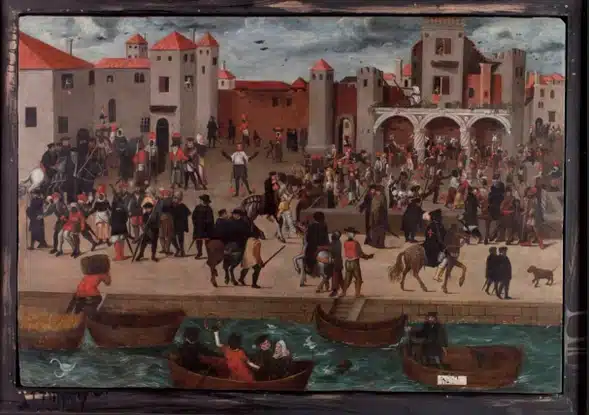

This notwithstanding, let’s not forget that for many, as it happens with Charles Boxer (1961, p.4) “Medieval Europe was a harsh and rugged school, and the softer graces of civilization were not more widely cultivated than elsewhere. A turbulent and treacherous nobility and gentry; an ignorant and lax clergy; doltish if hard-working peasants and fishermen; and a town rabble of artisans and day-labourers like the Lisbon mob described by Eça de Queiroz five centuries later, ‘fanatical, filthy, and feroucious’ – these constituted the social classes from which the pioneer discoveries and colonizers were drawn.”

“It may seem difficult to find a rational explanation for this surge, this cosmic curiosity, this craving for knowledge and understanding that then appeared to impel the Portuguese to discover the world.”[iii]

“At the risk of over-simplification, it may, perhaps, be said that the four main motives which inspired the Portuguese were, in chronological order, (i) crusading zeal, (ii) desire for Guinea gold, (iii) the quest for Prester John, and (iv) the search for spices.”(Boxer 1961, p.5-6) A mixture of Mammon, Caesar and God inspired motives, as the same author writes.

[i] Rui Tavares “Qual estado, qual nação?” in Público, October 9, 2017

[ii] Boxer, Charles Ralph “Four Centuries of Portuguese Expansion, 1415-1825”, Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg, 1961

[iii] Orlando Ribeiro, “Originality of the Portuguese Expansion” (Synopsis of “Originalidade da Expansão Portuguesa”, Edições João Sá da Costa, Lisboa, 1994, p.155 – written between 1954 and 1960)

Of the 2,047 Km long borders, 832 are by the seashore, and no place in continental Portugal is farther away than 218Km from the Atlantic Ocean.[i]

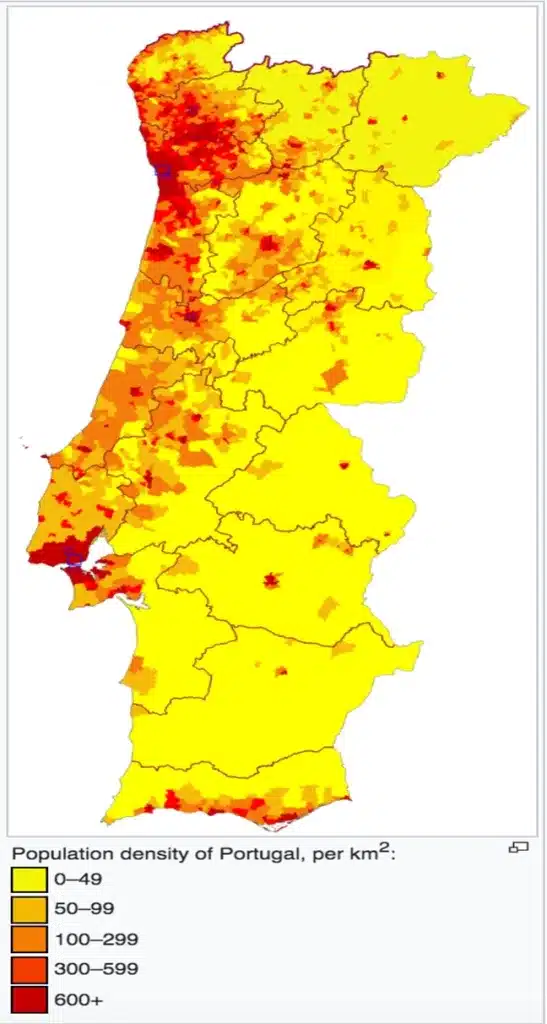

According to Armando Castro, population concentrated on the ocean shores and more on the north than the south since before the nationality was established.[ii]

There was a time when Portuguese influence spread around at least half of the world, from the Moluccas to Terra Nova[iii], from Uruguay to China and Japan.

Some even say, or at least do not exclude the possibility, that the first Europeans to reach today’s Australia were the Portuguese in the early16th century,[iv] more precisely 1521-2 under the command of Cristóvão de Mendonça[v], that Christopher Columbus was a Portuguese undercover agent in the service of the Portuguese king John, the Second, trying to distract the Castilians from the true path to India[vi], that before the Jamestown and the Mayflower settlers the Portuguese had already set foot on North American soil.

[i] Russell-Wood, A. J. R. “Portugal e o Mar: um Mundo Entrelaçado” Assírio & Alvim, 1997, p.7

[ii] Armando Castro “História económica de Portugal, vol. 2, Séculos XII a XV”, Editorial Caminho, Lisboa, 1978, p. 46

[iii] Fina d’Armada “Os Portugueses chegaram à América antes de Colombo? O misterioso Fagundes e a Terra Nova”, in Miguel Sanches de Baèna & Paulo Alexandre Loução (coord.) “Grandes enigmas da história de Portugal”, Ésquilo, vol. 1, 2008, p.467-497

[iv] John Tasker “Sixteenth Century Portuguese Down Under, vol.1-3, Kanuka Press, 2012, George Collingridge “The First Discovery of Australia and New Guinea”, Sydney 1906, Kenneth McIntyre “The Secret Discovery of Australia. Portuguese Ventures 250 Years Before Captain Cook”, Souvenir Press, 1977, Peter Trickett “Beyond Capricorn: How Portuguese Adventurers Secretly Discovered and Mapped Australia 250 Years Before Captain Cook”, East Street Publications, 2007, Richard Henry Major “The Discovery of Australia by the Portuguese in 1601.

Five years before the earliest discovery hitherto recorded: With arguments in favour of a previous discovery by the same nation, early in the sixteenth century”, J. B. Nichols and Sons, London, 1861, “Theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia” in Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_the_Portuguese_discovery_of_Australia), and for a somewhat more sceptical view see Albuquerque, Luis de (1990, p.87-103), “Dúvidas e certezas dos descobrimentos portugueses”, Vega, Lisboa.

[v] Susana Lima dedicates a whole chapter to this in “Grandes exploradores portugueses”, D. Quixote, 2012, p.69-83. Another hypothesis would be 1525 with pilot Gomes Sequeira sailing from Ternate. (A. J. Silva Soares “A ciência náutica e a expansão marítima portuguesa. Dúvidas, certeas, e deturpações históricas”, Academia da Marinha, Lisboa, 1997, p.325) This author reminds us that Portuguese presence in the island of Timor was official, and that this island was only some 70 leagues away from Australian shores.

[vi] Mascarenhas Barreto “The Portuguese Columbus. Secret Agent of King John II”, Macmillan, 1992

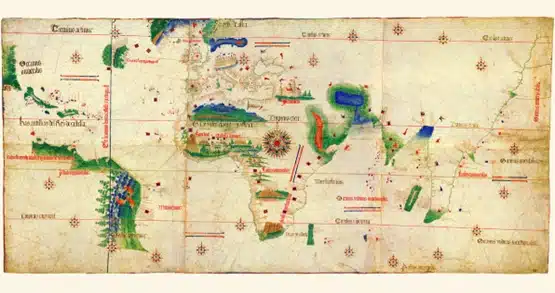

Cantino’s planisphere, according to Joaquim Alves Gaspar’s Dicionário das Ciências Cartográficas (2004) is a map designed by an anonymous Portuguese cartographer in 1502, and taken to Italy by Alberto Cantino, an agent of Hércule de Este, duke of Ferrara. It would be the first ancient chart to reflect the discoveries in the American continent by the end of the 15th century, as it pictured a big chunk of Brazil’s coastline, the Antillean islands, and some of what is known as Florida, isolating it clearly from Asia, as well as Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India even if this would have been only disclosed publicly 1506.[i]

Adam Smith, apparently following Raynal (“Histoire Philosophique”), poised in his “Wealth of Nations” (part 3 of chapter VII, second volume) that “The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind.” And chances are that two Portuguese were responsible for both of them.[ii] At least there is no contest of Bartolomeu Dias and/or Vasco da Gama being responsible for the second event. And both were Portuguese.

“Admiral Ballard, writing with a wealth of practical experience, declares that Vasco da Gama’s direct voyage to the cape in 1497 has a strong claim to rank as the finest feat of pure navigation ever accomplished. G. F. Hudson pertinently adds that if it had a rival, it is surely the voyage of Magellan, who was likewise a Portuguese.”[iii]

According to David Abulafia, “[f]rom the European perspective, da Gama’s voyage was the true success story. Columbus and Cabot were convinced that they had reached the edges of Africa, …”[iv] Even if “…India was a land of kings, of scheming Moors, of undoubted wealth, in which the Portuguese were not really welcome.

Da Gama’s attempts to negotiate with local rulers were frustrated at every turn, and his constant recourse to violence, which became the trademark of Portuguese conquerors, made it more difficult still to win the respect of local rulers and establish trading stations. Still, da Gama was able to leave loaded with samples of pepper and other goods, and to reach Lisbon again in September 1499.”

[i] Loução, Paulo Alexandre “O enigma do ‘Planisfério de Cantino’ e a ciência avançada dos Portugueses” in Miguel Sanches de Baèna & Paulo Alexandre Loução (coord.) “Grandes enigmas da história de Portugal”, Ésquilo, vol. 1, 2008, p.575-586

[ii] For more on the chance of Columbus being a Portuguese please take a look at respective chapter of this book/blog of mine.

[iii] Charles R. Boxer “The Christian Century in Japan. 1549-1650”, Carcanet, Manchester, 1993 (1951), p.2

[iv] “The Boundless Sea. A Human History of the Oceans”, Allen Lane, 2019, p.522

“In the year 1500, humanity stood on the threshold of the modern age. China’s retreat from world naval hegemony was followed by the entry of first the Portuguese and then the Dutch, French and English into Asian waters. Spanish vessels crossed the Atlantic to exploit the resources of the New World. The result was the creation of the first genuinely global economy.” (Moore & Lewis 2000, p.184)[i]

“The Portuguese were the quickest to adapt Italy’s prodigious market knowledge. Early in the 1400s Prince Henry the Navigator created an institute devoted to learning how to reach India by sailing around Africa.

Among the prince’s hired knowledge-workers were Europe’s finest astronomers, map-makers and sailors. In 1418, Portuguese ships began to follow the ancient trail of Hanno of Carthage, sailing down the shores of West Africa. The new caravels had three masts, triangular sails, rudders, compass adapted from the Chinese and the finest maps Italy could produce.” (Moore & Lewis 2000, p.187)

European history’s axis, dominated for two millennia by the Mediterranean Sea, now shifted dramatically to the Atlantic. While Italy fell under the curse of fierce political wars between French Valois and Spanish Habsburgs, Portugal opened a direct sea route to India and Asia, wresting the spice trade from Venetian hands and Islamic Arab hands.

The commercial dominance enjoyed by the Italian city-republics was doomed. Portugal developed a strong trading presence among the Indian, Chinese, Indonesian and other merchants of the Indian Ocean, which would last until the 1670s.” (Moore & Lewis 2000, p.187)

[i] Moore, Karl & David Lewis “Foundations of Corporate Empire. Is History Repeating Itself?”, Prentice Hall, London, 2000

Some claim even that Portugal – the “first and oldest” unified nation in Europe (Kaplan 2006, p.55) – was the “first hegemonic power of global reach.” [my own translation] (Rodrigues & Devezas, 2007, p.47) To discuss the New World without mentioning the Portuguese “is something like writing about the space age while ignoring the American space program.” (Maxwell 2003, p.30-31)[i] And the Russian/Soviet one for that matter, I would add.

“It is therefore worth recalling that precisely during the long hiatus while the Catholic monarchs sought to confirm Columbus’s claims to have reached Asia, the Portuguese, in fact, reached India, and King Manuel of Portugal (1495-1521) wrote in 1499 to inform his Castilian colleagues of his claims to the ‘suzerainty and dominion of the navigation, and commerce, of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, and India.’ This was of course hyperbole – but it demonstrated that the Portuguese had done in fact what Columbus claimed to have done – reach Asia by sea.” (Maxwell 2003, p.32)

Maxwell (2003, p.33) writes of the “no more than fifteen years, in which the Portuguese reached the Seychelles, Socotra [Yemen], and the coast of Arabia (1503), Ceylon and the Bay of Bengal (1509). In the Pacific they explored the coast of Southeast Asia and reached China in 1513. Contact with Japan came during the 1540s.

And even in the Americas, Portugal arrived at nowadays’ Brazil in 1500.” And Maxwell goes on: “With this first period of oceanic contact an entirely new way of viewing the world emerged and the Portuguese were in large part responsible for it. They established an oceanic dominion that linked strategically placed trading posts in a worldwide imperial system.” (ibidem p.34)

[i] Maxwell, Kenneth “Naked Tropics. Essays on Empire and Other Rogues”, Routledge, 2003

Portugal counted less than 2 million inhabitants and was arguably “one of the less ‘advanced’ countries in Europe at the time it began its expansion, and indeed much less prosperous than northern and central Italy, France or Spain. In all of Iberia, Portugal, or the regions which was to become known as Portugal later, was the last area to resist the Romans, the last to be incorporated into the empire of the Visigoths, the last to adopt the Christian calendar, and the last to adopt titles for its nobility in accordance with what obtained elsewhere.” (Subrahmanyam 1993, p.144)[i]

“To dispel these prejudices from our minds, we must therefore be reminded of the great and glorious record of the Portuguese in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries – the age in which this small country sprang to pre-eminence among the nations of Europe, discovered the whole world, became mistress of half the world, established an empire that was larger than the Roman Empire and lasted longer than the British Empire, climbed to the dazzling wealth of her Manueline period, and opened the eyes of men to the new way of life, ushering in the modern age.” (McIntyre 1977, p.4)

Some like Maia[ii] (1941, p.125) even claim to my recent surprise and bemusement that Portuguese pilots were the first to sail through the Arctic Sea blazing the trail of both the North-West and North-East passages.

“The Portuguese have always shown a remarkable ability to accommodate even the most exotic of foreign elements with their own. They were the first to introduce the Orient to Europe. Yet they remain distinctly Portuguese. Conformity alternates (and blends) with great bursts of originality.

They are great improvisers and adapters, pasticheurs. It is a pattern of contrasts and contradictions, a mixing process, an originality verging on the eccentric, which fascinates me, and when one can trace and follow its distinctive style, flavour and pattern around the world in a multitude of different settings, as I have attempted to do, it becomes a kind of Odyssey.” (Teague 1988, p.20)

Others describe the way the Portuguese interacted with locals in Africa and elsewhere: “It would not be a gross over-simplification to say that here, as in many places, Portuguese activities consisted of alternatively fighting, trading, and fornication with the local inhabitants.” (Boxer 1961, p.35)

A long and declining way to the current situation of poorest country of Western Europe, again!

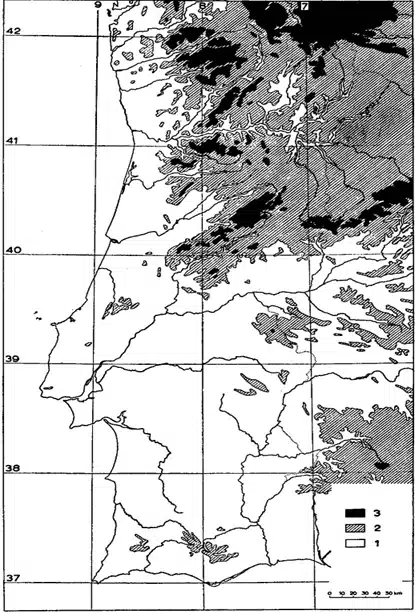

Before we delve further into history and elsewhere, let’s first characterize the country geographically following mostly Orlando Ribeiro’s “Portugal. O Mediterrâneo e o Atlântico. Esboço de relações geográficas” (Livraria Sá da Costa, 1987 (1945). As implied in the title and paraphrasing Pequito Rebelo “Portugal is Mediterranean by nature, and Atlantic by location/position”, where the North/South, and the coast/inland divide, are paramount.

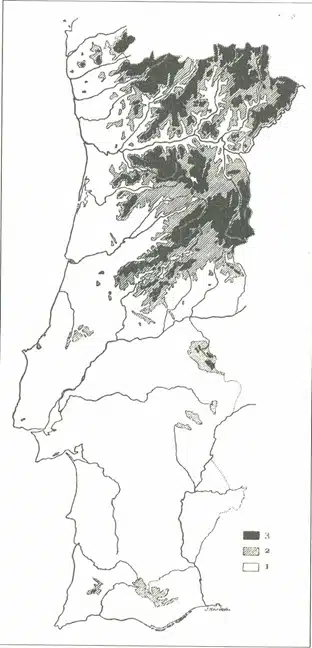

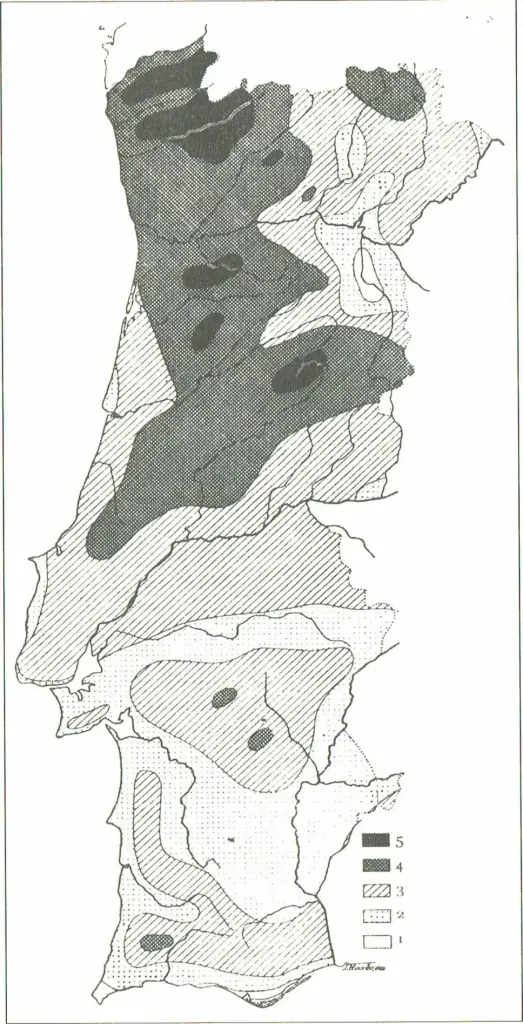

The North being a lot more mountainous than the flat South (20% of the area north of the river Tejo – the most common dividing line – lies above 700 meters of altitude, against 0.2% south of it), more densely populated, cooler, more humid and rainy, and with smaller land properties.

[i] Subrahmanyam, Sanjay “The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500-1700: A Political and Economic History”, Longman, London & New York, 1993

[ii] Maia, Carlos Roma Machado de Faria e (1941), “A primeira volta ao mundo pelos mares glaciais do norte foi dada por dois pilotos portugueses João Martins e David Melgueiro em 1585 e 1660”, Gazeta dos Caminhos de Ferro 1276, p.125

The 3 biggest towns are harbours, and from the 20 or so largest urban agglomerations only 2 (to 4) are far from the coast. Historically the South shows a lot more Roman and Islamic influences than the North, being this area a lot more religious – mainly Catholic – than the South. Besides the Tejo/Tagus river, the Mondego and Douro can also be considered significant dividing lines.

In terms of vocabulary, and partially reflecting the longer presence of Muslims in the South, the Arabic origin of many Portuguese words still in use is a lot more prevalent in this area than in the North.

[1] Synopsis of “Originalidade da Expansão Portuguesa”, Edições João Sá da Costa, Lisboa, 1994, p.155 – written between 1954 and 1960

[1] Rui Tavares “Qual estado, qual nação?” in Público, October 9, 2017

[1] Boxer, Charles Ralph “Four Centuries of Portuguese Expansion, 1415-1825”, Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg, 1961

[1] Orlando Ribeiro, “Originality of the Portuguese Expansion” (Synopsis of “Originalidade da Expansão Portuguesa”, Edições João Sá da Costa, Lisboa, 1994, p.155 – written between 1954 and 1960)

[1] Orlando Ribeiro, “Originality of the Portuguese Expansion” (Synopsis of “Originalidade da Expansão Portuguesa”, Edições João Sá da Costa, Lisboa, 1994, p.155 – written between 1954 and 1960)

[1] Russell-Wood, A. J. R. “Portugal e o Mar: um Mundo Entrelaçado” Assírio & Alvim, 1997, p.7

[1] Armando Castro “História económica de Portugal, vol. 2, Séculos XII a XV”, Editorial Caminho, Lisboa, 1978, p. 46

[1] Fina d’Armada “Os Portugueses chegaram à América antes de Colombo? O misterioso Fagundes e a Terra Nova”, in Miguel Sanches de Baèna & Paulo Alexandre Loução (coord.) “Grandes enigmas da história de Portugal”, Ésquilo, vol. 1, 2008, p.467-497

[1] John Tasker “Sixteenth Century Portuguese Down Under, vol.1-3, Kanuka Press, 2012, George Collingridge “The First Discovery of Australia and New Guinea”, Sydney 1906, Kenneth McIntyre “The Secret Discovery of Australia. Portuguese Ventures 250 Years Before Captain Cook”, Souvenir Press, 1977, Peter Trickett “Beyond Capricorn: How Portuguese Adventurers Secretly Discovered and Mapped Australia 250 Years Before Captain Cook”, East Street Publications, 2007, Richard Henry Major “The Discovery of Australia by the Portuguese in 1601.

Five years before the earliest discovery hitherto recorded: With arguments in favour of a previous discovery by the same nation, early in the sixteenth century”, J. B. Nichols and Sons, London, 1861, “Theory of Portuguese discovery of Australia” in Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_the_Portuguese_discovery_of_Australia), and for a somewhat more sceptical view see Albuquerque, Luis de (1990, p.87-103), “Dúvidas e certezas dos descobrimentos portugueses”, Vega, Lisboa.

[1] Susana Lima dedicates a whole chapter to this in “Grandes exploradores portugueses”, D. Quixote, 2012, p.69-83. Another hypothesis would be 1525 with pilot Gomes Sequeira sailing from Ternate. (A. J. Silva Soares “A ciência náutica e a expansão marítima portuguesa. Dúvidas, certeas, e deturpações históricas”, Academia da Marinha, Lisboa, 1997, p.325) This author reminds us that Portuguese presence in the island of Timor was official, and that this island was only some 70 leagues away from Australian shores.

[1] Mascarenhas Barreto “The Portuguese Columbus. Secret Agent of King John II”, Macmillan, 1992

[1] Loução, Paulo Alexandre “O enigma do ‘Planisfério de Cantino’ e a ciência avançada dos Portugueses” in Miguel Sanches de Baèna & Paulo Alexandre Loução (coord.) “Grandes enigmas da história de Portugal”, Ésquilo, vol. 1, 2008, p.575-586

[1] For more on the chance of Columbus being a Portuguese please take a look at respective chapter of this book/blog of mine.

[1] Charles R. Boxer “The Christian Century in Japan. 1549-1650”, Carcanet, Manchester, 1993 (1951), p.2

[1] “The Boundless Sea. A Human History of the Oceans”, Allen Lane, 2019, p.522

[1] Moore, Karl & David Lewis “Foundations of Corporate Empire. Is History Repeating Itself?”, Prentice Hall, London, 2000

[1] Maxwell, Kenneth “Naked Tropics. Essays on Empire and Other Rogues”, Routledge, 2003

[1] Subrahmanyam, Sanjay “The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500-1700: A Political and Economic History”, Longman, London & New York, 1993

[1] Maia, Carlos Roma Machado de Faria e (1941), “A primeira volta ao mundo pelos mares glaciais do norte foi dada por dois pilotos portugueses João Martins e David Melgueiro em 1585 e 1660”, Gazeta dos Caminhos de Ferro 1276, p.125

[1] 1 – Below 400 meters, 2 – Between 400 and 900 meters, 3 – above 900 meters. From: Orlando Ribeiro, 1987, p.179

[1] From Orlando Ribeiro “Portugal, o Mediterrâneo e o Atlântico”, Livraria Letra Livre, Lisboa, 2011, p.215. 1 – Below 400 meters, 2 – Between 400 and 700 meters, 3 – above 700 meters.

[1] From Orlando Ribeiro “Portugal, o Mediterrâneo e o Atlântico”, Livraria Letra Livre, Lisboa, 2011, p.217. 1 – Below 400 mm, 2 – Between 400 and 600 mm, 3 – Between 600 and 1000 mm, 4 – Between 1000 and 2000 mm, 5 – Above 2000 mm.

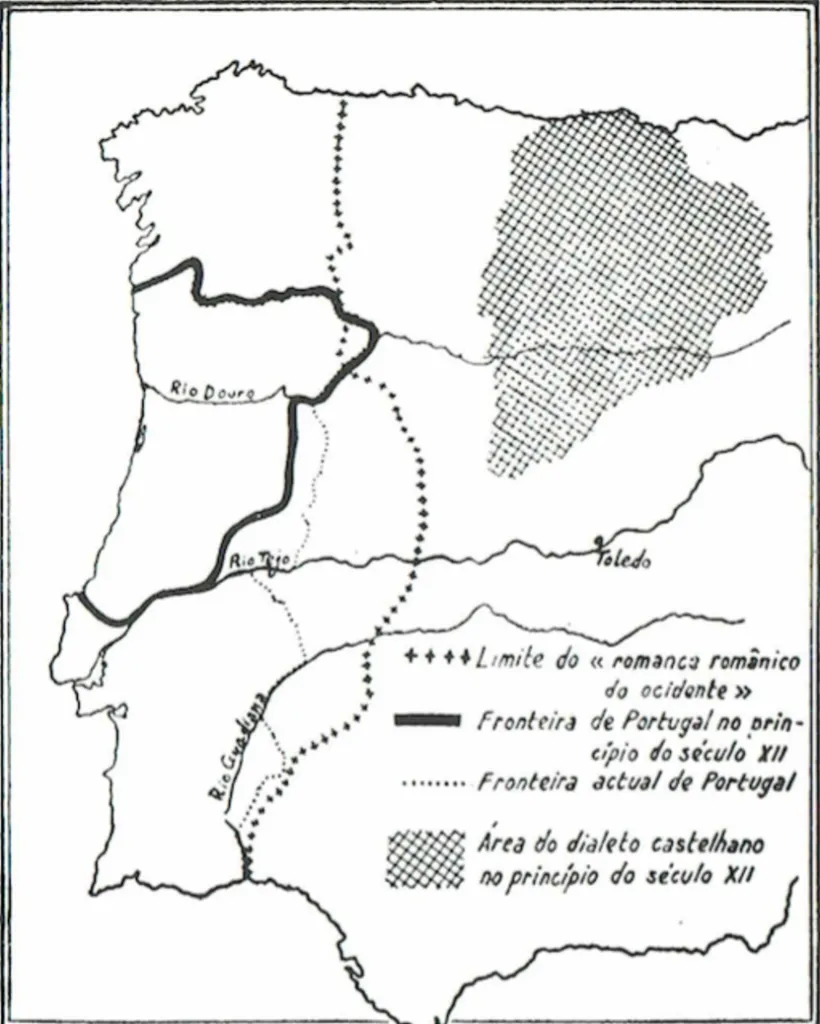

[1] From Damião Peres “Como nasceu Portugal”, Vertente, Porto, s.d., p.33

[1] From Wikipedia, as accessed August 24, 2020