Japan. The Namban Screens and Wenceslau de Moraes

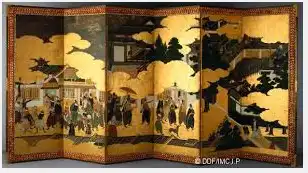

These painted folding screens – “biombo” in Portuguese, derived from the similarly sounding Japanese word “biô-bu” [byōbu (南蛮屏風)] – portray the arrival/presence of Portuguese in 16th century Japan. Namban, or Nanban-Jin, meaning barbarians[1] from the South, as they were known, arrived in Japan in 1543. 93[2] of these screens have been located and identified.[3] Thomaz (1993, p.68) mentions “today 63 known examples of nanban screens”, 6 of which were at the Portuguese National Antique Art Museum in Lisbon.

On these screens “are painted scenes with foreign ships, parties of Portuguese landing from their vessels and strolling about ashore, churches in Japan, etc.”[4] “There are other Byobus painted with a world map, a battle scene between Christians and Mohamedans, the Battle of Lepanto, European cities – Lisbon, Rome, Madrid, Constantinople – European musicians, etc.

Their composition is remarkable and shows such broad vision, uncommon in Japanese paintings, that they could be said to be the product of a modern mind, influenced by European art of the 17th century.”[5] They would be kept “in the museums of Lisbon, Porto, in the USA and in England, but most of them have remained in Japan. They were painted between 1600 and 1630, and the Japanese port usually shown is said to be Nagasaki.”[6]

“The entry of the Portuguese into the hermetic society of Japan was responsible for one of the most notable chapters in the art of the Far Eastern nation: Nambam, the art of the ‘barbarians from the South’ (namban-jin). While maintaining all their traditional materials and forms the artists of Nippon were able to capture snapshots of the daily lives of the Portuguese merchants, dignitaries and missionaries who frequented their ports and use them as decorations on furniture – the delicate screens destined for the palaces of feudal lords of their land.

Through their images we have inherited the most complete eyewitness accounts of our predecessors, created by contemporaries of another civilisation, which finds but a pale imitation in the literary testimony of the Pilgrimage by Fernão Mendes Pinto, when he comments upon the appraisal made by the Portuguese by the civilisation of the Other.” (Pereira 1996, p. 264)

“The nanban screens reveal a whole world. On the shoulders of the Portuguese perch falcons and monkeys. With their riders or held by the halter we can admire graceful Persian horses, which the Portuguese from their trading post at Hormuz sold all over the Orient, for there was a steady demand for them.

An animal often represented is the dog. …Other fauna are more exotic: in cages there are birds, difficult to identify, and animals with fur, leopards it seems; outside stroll camels, never before seen in the country, and elephants brought from Ceylon or India, … Here we see a man leading two donkeys; there, before Portuguese reclining in Chinese style chairs and smoking pipes, a fine Indian peacock displays his tail; elsewhere, on the quarterdeck a man carries a little rabbit in his arms.” (Thomaz 1993, p. 75-6)

Charles Boxer (1993-1951, p.200) credits the namban screens to the Kano, Tosa, Sumiyoshi schools in the Keicho era (1594-1618).

[1] “[T]he character yi, ‘barbarian’, was the normal Chinese word applied to all non-Chinese peoples.” Nigel Cameron “Barbarians and Mandarins. Thirteen centuries of Western Travelers in China”, Walker/Weatherhill, New York & Tokyo, 1970, p.13

[2] Janeira estimates that only “little more than half hundred” were left. Armando Martins Janeira, “O impacto português sobre a civilização japonesa” Dom Quixote, Lisboa, 1988 (1970), p.177

[3] Miki, Yoshi “Namban Screens in the 21st Century” in Namban Screens, Museu Nacional de Soares dos Reis, 2009, 67-76 and Maria Helena Mendes Pinto “Namban Screens” Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 1993. For a detailed description and interpretation of a dozen of the most representative folding screens hold by several museums and private collections around the world you may check Alexandra Curvelo’s “Nanban Folding Screen Masterpieces. Japan-Portugal XVIIth Century” published in Paris by Chandeigne in 2015.

[4] Kiichi Matsuda “The Relations Between Portugal and Japan”, Junta de Investigações do Ultramar and Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, Lisbon, 1965, p.89

[5] ibidem

[6] ibidem

Japan first met Europe in 1543, when a storm blew a Chinese ship with Portuguese traders[1] on board to the outlying island of Tanegashima, in the Kagoshima Prefecture. [Some say in Kyushu] Two revolutionary novelties accruing to Japan from that chance encounter are well known — firearms and Christianity.

A third, says Kitahara, was the slave trade. Before long Japanese slaves were being bought and sold not only throughout Asia but as far afield as Portugal and Argentina.” (Michael Hoffman “The rarely, if ever, told story of Japanese sold as slaves by Portuguese traders”, The Japan Times, May 26, 2013 commenting on “Portuguese Colonialism and Japanese Slaves” by Michio Kitahara, Kadensha, 2013)

Bernardo, the Christian name of the first Japanese to become a Jesuit, and allegedly the first Japanese to set foot in Europe, travelled to Portugal and landed in Lisbon in September 1553 and died in Coimbra in 1557. (Matsuda 1965, p.7) Ômura Sumitada became 1563 the first Christian daimio. (Costa 1999 p.61 and 1993, p.23)

Soares (1997 p. 339-340), Costa[2] (1993 p. 50-51) and Cooper (1974, p.70-72) recount the visit by 4 young Daimio family members with friendly relations with the Portuguese, who have been brought to Europe for an 8 years long visit between 1582 and 1590. They visited Macau (1582), Malaca, Goa, Cochin (1583), Lisbon (1584), Alcobaça, Batalha, Sintra, Évora, Vila Viçosa, Madrid/Escorial, where they were received in audience by king Philip II, Toledo, and Rome (1585), where they met with the pope. A press/printer would have accompanied them on their trip back to Japan, where they arrived in Nagasaki (1590), and where the Jesuits started their printing activities.

“It was about this time that the craze for European fashions reached its peak in Japan, and when Hideyoshi set out from Nagoya on his way back to the capital, the members of his retinue were dressed in Portuguese style. Largely as a result of Valignano’s embassy in 1591, every Japanese at court made efforts to obtain at least one article of European dress; some nobles even possessed complete wardrobes of cloaks, capes, ruff shirts, breeches, and hats.”…”

The craze was not confined to styles of clothing but also extended to diet; the practice of eating veal, which had earlier caused so much abhorrence among the Japanese, grew in popularity and the great Taikō himself expressed his liking for this dish. Enthusiasm for European practices went so far that even non-Christians sometimes carried rosaries and learned the Pater Noster and Ave Maria by heart nerely to keep up with the Japanese Joneses.”[3]

Fire arms, like the musket, were also introduced or at least popularized, by the Portuguese and played an eminent role in the civil strife conducting to the unification of Japan under the same political power, personified by Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Hospitals and fight against then in Japan generally accepted infanticide and abortion were also part of Portuguese influence.[4]

“Within less than 20 years [after their arrival 1542 or 1543] a lucrative trade had been built up by Portuguese merchants, who exchanged Chinese silk for Japanese silver and made large fortunes in the process.”[5]

“At the end of the sixteenth century,[6] was already the safe port for the Black Ship [kurofone or kurofune][7], a fundamental center for Macao-Japanese commerce and the main base of operations for merchants and Western missionaries.” (Curvelo, 2015 p.7) This so-called ‘black ship’ (carrack, or nau in Portuguese, in this case nau do trato, called ‘the great ship from Amacon[Amacao]’ by the English according to Curvelo 2015, p.71) was the “central protagonist of these paintings”. (idem, p.5)

The Ming emperor’s ban on direct commerce between China and Japan would have “put the Chinese merchants at a great disadvantage”, as they “could only trade officially with their Japanese neighbours through the medium of the Portuguese, who, in addition to being (prior to 1600) the only important source of supply for European and Indian goods for Japan, likewise enjoyed a virtual monopoly of the Chinese silk export market which was far and away the most profitable part of the Sino-Japanese commerce.”[8]

The Portuguese introduced the ‘tempura’ (tempero or tempora)[9] and above all the valuable refined sugar, creating nanbangashi (南蛮菓子?), “Southern barbarian confectionery”, with confectioneries like panderó (for pão de ló), castella or castera (from claras em castelo), pate (for pastel), konpeitō, aruheitō, karumera or karumero (for caramelo), keiran sōmen, bōro (for bolo), doses (for doces), and bisukauto or bisukoito (for biscoito).

After first exporting gold, silver was the main export product from Japan, followed by copper, wheat and lacquered goods, like lacquer cabinets, boxes and furniture, painted gold-leaf paper screens (byobu, hence the Portuguese biombo, kimono, swords, pikes and shipping material, which were traded against raw silk and silken fabrics (brought in mainly from China), velvet and other textiles, pottery, leather, lead, musk and twisted thread, gold (mainly from China too), horses from Persia, porcelain, spices, ivory, wine, gunpowder, sand-glasses, spectacles, embroidered kerchiefs, preserved fruit, honey, tools made in China, hats, carpets and other products. (Janeira 1988, p.120, Boxer 1948, p.16 and Matsuda 1965, p.12 and 93-94)

“It should be pointed out that all the imports into Japen came from China and the South Seas” (Matsuda 1965, p.12), and that none or scarcely any products were brought in from Europe. (Janeira 1988, p.143)[10]

“The reason why the trade proved so profitable was that silver was worth much more in China than in Japan, whereas the contrary was true of silk; since the Ming Court prohibited all direct trade between the two empires, the Portuguese cashed in as the indispensable middlemen.” (Boxer 1948, p.16)

Medicine (namban igaku), including medical science and surgical treatment – the first hospital in Japan would have been built by the Jesuits,[11] astronomy, meteorology, geography, naval construction and seamanship, cartography, arts, printing[12] and the printing press, education and science were the main fields of expertise shared with the Japanese (Janeira ibidem p.163-175, Soares 1997, p.340-1 and Matsuda 1965, p.65 and following), with a special addition of weapons, muskets, and other guns and gun powder, which became of paramount importance in Japanese domestic conflicts, having been highly instrumental in contributing to the unification of political power in 1600.

“European music seems to have reached Japan at the same time as the Portuguese” and episodes of marches with bands, boys’ choirs during mass, hymns, and songs in Japanese based on stories from the Bible were popular, according to Matsuda (1965, p.91-92), who mentions that “instruments such as the harpsichord, the organ, the lute and the bagpipe were imported into Japan and taught at the Seminary” by then and that stage plays based on biblical and gospel schenes were performed on special Catholic occasions.

“Europe sent to Japan not only Portuguese merchants but also Catholic missionaries; and in the summer of 1549, Saint Francis Xavier and two other members of the newly founded Society of Jesus arrived in the Kyushu port of Kagoshima and started the work of evangelization. In succeeding years more Jesuits began working in the Japanese mission; although by 1577 they still numbered less than forty, the missionaries achieved remarkable results, and numerous Christian communities were established throughout the country.”[13]

By 1560 only a few thousand converted Christians and 6 churches were estimated to exist In Japan; ten years later there would be more than thirty thousand Christians and 36 churches. (Costa 1993, p.30) Between 1570 and 1582 the number of Christians would have increased fivefold from 30 to 150 thousand, and 1587 they would have numbered around 200 thousand. (Costa 1993, p. 42 and 1999, p.177, Cooper 1974, p.108)[14]

Friar Fernão Guerreiro estimated the number of Christian converts in all of Japan to have reached 750,000[15] in 1605. (Thomaz 1993, p.117) “In 1596 there were thus in Japan 140 priests and 300 000 Christians”. (Thomaz 1993, p.115 and Janeira 1988, p.54) In 1582 “there were in Japan 20 priests and 30 brothers, 200 churches and 150,000 Christians.” (Thomaz 1993, p.111)[16]

The missionaries would keep a school close to each church and Janeira estimates that around 1583 there would be around 200 of those schools with 12 thousand students. (ibidem p.163) Up to 90 per cent of missionaries were at a time Japanese born. (Soares 1997[17] p.337) In 1603 from the 120 members of the Jesuit mission 50 were Japanese, in 1607 among 138 missionaries 68 were Japanese, and in 1612-3 among the 121 Jesuits 54 were from Japanese extraction.[18]

Around 1605-1614 estimates of Christian population in Japan vary between 250,000 and 2 million, and a total number of missionaries – 143 – among a total population of about 20 million. …”it would be difficult, if not impossible, to find another highly civilized pagan country where Christianity had made such a mark, not merely in numbers but in influence.” (Boxer 1993, p.320-1)

Jesuit Francis Xavier arrived at Kagoshima in 1549 with some followers, and public acceptance was so widespread that the Jesuit mission in Japan was for a time the largest overseas. (Soares ibidem) It was the so-called Christian Century of Japan.[19] By the end of the 15th century no other part of the overseas world controlled by local powers, i.e. completely disconnected from European politico-military influence, existed a so numerous Christianity served by a religious team with a predominantly native face.[20]

According to Costa (1993, p.8), Portugal would have been the only foreign people with whom the Japanese had intensely and enduringly socialized in Japan before the end of the 19th century. After having established themselves in Macau (China, 1557) the trade route from here to Nagasaki[21] (Japan) started 1569 and was formalized 1571, after having previously tried other harbors/regions, like Satsuma, Hirado, Bungo, Hizen, Yokoseura and Fukuda (Omura), Kuchinotsu (Arima) on different occasions/years. (ibidem p. 22-23 and Boxer 1948, p.16)

[1] Charles Boxer calls them ‘deserters’ and dates this back to 1542. (“Fidalgos in the Far East, 1550-1770. Fact and Fancy in the History of Macao”, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, 1948, p.2-3)

[2] João Paulo Oliveira e Costa “Portugal e o Japão. O século Namban”, Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 1993

[3] Cooper 1974, p.104

[4] João Paulo Oliveira e Costa “O Japão e o cristianismo no século XVI. Ensaios de história luso-nipónica”, Sociedade Histórica da Independência de Portugal, Lisboa, 1999, p.71-79. Boxer (1993-1951, p.203) the hospital for the care of lepers and syphilitics at Oita (Funai) founded by a Jesuit of ‘New Christian’ origin, together with an orphanage for the care of destitute children, “was the first of its kind ever erected in Japan, and patients flocked to it from far and wide.”

[5] Michael Cooper “Rodrigues the Interpreter. An early Jesuit in Japan and China”, Weatherhill, New York and Tokyo, 1974, p.18

[6] Founded 1571 by/for/with the Portuguese, had already 400 houses in 1579, 5 thousand inhabitants in 1590 and 15 thousand in 1600, (Please see Costa 1993, p. 39-41 for these and other details about Nagasaki) after becoming “the main port for Japan’s overseas trade for nearly three hundred years”, after its foundation 1571. (Boxer 1948, p.38)

[7] “The Japanese called these Carracks and galleons, Kurofune[or Kurobune] or ‘Black Ships’, presumably because of the colour of their hulls, and this name was revived for Commodore Perry’s ships 3 centuries later. They evidently made a great impression, as well as they might, being the largest ships then afloat on the Seven Seas.” “…[t]he ‘Great Ship from Amacon’ [Macao] was the largest ship in the world in its day and generation, and if only for this reason its memory desserves rescuing from oblivion.” (Boxer 1948, p.20; see also this author’s “The Great Ship from Amacon. Annals of Macao and the Old Japan Trade”, Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, Lisboa, 1963)

[8] Charles Boxer 1948, p.5-6

[9] “It came about as a way to fulfill abstinence and fasting requirements for Catholics surrounding the Ember Days (in Latin: Quatuor Tempora).” … “The word “tempura”, or the technique of dipping fish and vegetables into a batter and frying them, comes from the word “tempora”, a Latin word meaning “times”, “time period” used by both Spanish and Portuguese missionaries to refer to the Lenten period or Ember Days (ad tempora quadragesimae), Fridays, and other Christian holy days. Ember Days or quattuor tempora refer to holy days when Catholics avoid red meat and instead eat fish or vegetables.[7]

The idea that the word “tempura” may have been derived from the Portuguese noun tempero, meaning a condiment or seasoning of any kind, or from the verb temperar, meaning “to season” is also possible as the Japanese language could easily have assumed the word “tempero” as is, without changing any vowels as the Portuguese pronunciation in this case is similar to the Japanese.[8] There is still today a dish in Portugal very similar to tempura called peixinhos da horta, “garden fishes.”, which consists in green beans dipped in a batter and fried.” (From Wikipedia as accessed August 19, 2017)

[10] Soares (1997 p.342) mentions that an extensive group of manufactured and agricultural products would be brought in from Europe. This author specifically lists buttons, glass objects, namely eyeglasses, wine and olive oil, which would be previously unknown to the Japanese. From elsewhere would also come elephants (from India), camels (from the Middle East), ivory (from Africa), tobacco (from 1605), and coffee.

[11] Luis de Almeida, trader, physician and later a missionary, would at his expenses have built 1556 a large hospital attached to the Funai mission, where Western medicine would also have been tought.

[12] The first book for use in Japan would have been printed in Lisbon, and 29 books of which copies exist would have been printed in Japan. (Matsuda 1965, p.79 and 81)

[13] Cooper 1974, p.18-19

[14] “In addition to 113 European and Japanese Jesuits in Japan in 1587, there were about 150 dojuku or cathechists, and a community of nearly 200,000 converts. Backsliders from the Faith as a result of Hideyoshi’s edict were soon atoned for by fresh conversions, principally in Konishi’s fief of Higo (Udo).” (Boxer 1993, Note 9, p.470)

[15] Considered probably an exagerated estimate by Armando Martins Janeira (“O impacto português sobre a civilização japonesa” Dom Quixote, Lisboa, 1988 (1970), p.57 and 153), and which would be equivalent to around 4 per cent of the entire population.

The presence of 143 missionaries was also estimated by this author for that same year of 1605, who for ‘today’ – meaning in the 1960s – estimates that around 300 thousand ‘converts’, tantamount to 0.3 per cent of total population, would be accompanied by 1237 foreign priests, 477 Japanese and 4700 missionaries. Boxer (1993 p.187) also mentions the estimate of 750,000 “believers” by 1606, “with an average annual increase of five or six thousand, and Nagasaki could vie with Manila and Macao for the title of the ‘Rome of the Far East’.

[16] Numbers corroborated by Janeira, following estimates by the Jesuit Valignano (ibidem p.49) Cooper (1974, p.120) estimates that only 59 Jesuits were in Japan in 1580, “of whom 28 were priests and 31 were Brothers or scholastics. Ten years later this number had increased to 140 Jesuits, two-thirds of whom were unordained and therefore unable to celebrate Mass or administer the sacraments.”

[17] A. J. Silva Soares “A ciência náutica e a expansão marítima portuguesa. Dúvidas, certezas, e deturpações históricas”, Academia da Marinha, Lisboa, 1997

[18] João Paulo Oliveira e Costa “O Japão e o cristianismo no século XVI. Ensaios de história luso-nipónica”, Sociedade Histórica da Independência de Portugal, Lisboa, 1999, p.106

[19] C. R. Boxer “The Christian Century in Japan 1549-1650”, Carcanet, 1993 (1951)

[20] João Paulo Oliveira e Costa “O Japão e o cristianismo no século XVI. Ensaios de história luso-nipónica”, Sociedade Histórica da Independência de Portugal, Lisboa, 1999, p.43

[21] Nagasaki, or literally translated Long Cape. (Boxer 1993, p.105)

From 1586 missionary activities started to be considered undesirable political intromission. (Soares 1997 p.337) In 1597, 26 Christians/Catholics, among whom 4 Spanish, 1 Mexican, 1 Indo-Portuguese and Japanese Franciscans and laymen, were executed in Nagasaki[1], the first Dutch ship[2] arrives in 1600 spreading the word against Catholics, and quite a few other persecutions, executions, martyrdoms and pogroms followed[3], before Catholicism was officially outlawed around 1630-1640, (or 1614 as in Soares 1997 p.338?) and went underground.[4]

A couple of Portuguese diplomatic initiatives soon thereafter have not succeeded in re-establishing relations between both countries. Soares (1997, p.338) mentions the Portuguese embassy of 61 members coming in from Macau, 48 of whom were decapitated for not renouncing their faith and infringing then current restrictions on access by foreigners to Japan, having the remaining 13 been sent back to Macau in order to tell the story.

[1] Cooper 1974, (p.135 and following). 6 Franciscans, 3 Japanese Jesuitic brothers, and 17 Japanese lay Christians, because of suspitions raised by a Spanish pilot of a ship sunk near the Shikoku coast. This would also have triggered the process leading to the new anti-Christian edict by the kampaku Hideyoshi and subsequente supression of the Franciscan mission in Japan. (Costa 1993, p.68)

[2] The ship’s pilot, Englishman Will Adams, “was destined to play a significant role in Japan” and “was not allowed to leave Japan because of his valuable services as shipbuilder…”. (Cooper 1974, p.205) At the age of 49, Rodrigues was evicted from Japan/Nagasaki, after 33 years there, spent the remaining 23 years of his life in China/Macao, and was “unofficially succeeded in his capacity as court interpreter and trade negotiator” by Will Adams. (Cooper 1974, p.267)

[3] Namely the one mentioned by Soares (1997, p.338) where thousands would have been sacrificed 1622-1623 in Nagasaki. Costa (1999, p.296) estimates that from 1614 on around 2 thousand Christians would have lost their lives because of their faith in all of Japan. Boxer (1993 p.360-1) gives a maximum of 5 to 6 thousand Christiam mkaryrs for the whole 1614-1640 period.

[4] Between 1614 and 1643 from the 2 to 5 thousand killed Christians less than 70 were Europeans. Armando Martins Janeira, “O impacto português sobre a civilização japonesa” Dom Quixote, Lisboa, 1988 (1970), p.68.

Apprehensive about the spread of Christianity, Toyotomi Hideyoshi published a first anti-Christian edict in 1587[1], whereby he expelled all Christian missionaries from Japan, forbade the diffusion of Christianism in Japan, and tried to constrain the Portuguese to exclusive trade activities,[2] and the Japanese rulers have decreed again the expulsion of all Portuguese and Spanish missionaries in 1610 (religious orders were expelled from Japan in 1614, and the Portuguese altogether in 1639/40[3], according to Curvelo 2015, p.42 and Thomaz 1993, p.126).

Soon after, the Dutch set up a trading house (factory) at Hirado and two Dutch ships helped to bring a rebellion by local Christians at S(h)imabara, in the south of the island of Kyushu or Shimo, down to its knees in 1637 (Thomaz 1993, p.124).[4]

Janeira (ibidem p.61) and Soares (1997 p.338) describe how the Dutch would have been instrumental in defeating the Catholic inspired Shimabara rebellion (1637), which would have taken hold of the Hara castle, on the island of Ximo. Following their surrender already in the year of 1638, around 37 thousand insurgents would have been killed by the sword. This would have marked the effective end of Portuguese presence in Japan.

According to Matsuda[5], however, “[t]he Shimabara revolt, to which the Tokugawa government, for propaganda purposes, gave the high-sounding title of the ‘Christian Revolution’, had no direct connection with the Christians but was a common peasant uprising.

The government, however, used it as a further evidence of the Christian plot to conquer Japan.” Portugal was too closely connected to Christianity, which was banned from Japan for fear of interference with established local religions, like Confucionism and Budhism – Hideyoshi was himself a Shintoist and Tokugawa a Buddhist. Christian countries were known for their conquering ambitions, which could get in the way of the establishment of a powerful central political system by then under way. (ibidem p. 57-59)

The first English vessel, the Clove, arrived 1613 in Japan at Hirado, and the East Indian Company (EIC) was authorized to set up a trade factory in that harbour. The Dutch and the English suffered from the fact not to have established a trading post in China and of not yet having established a trade network in East Asia. (Costa 1993, p. 78).

The British would have subsequently closed down their factory at Hirado in 1623 and abandoned trade with Japan, consecrating the victory of the VOC over the EIC in East Asia. (Costa 1993, p. 81) “The Dutch and the English who arrived in Japan in 1600 influenced the Tokugawa government against the Portuguese and the Spaniards” (Matsuda 1965, p.100), as you would expect…

The animosity of Japanese rulers towards the Portuguese presence is attributed by Janeira (ibidem p.54) at least in part to the misunderstandings between the different Catholic religious orders involved in evangelizing Japan (mainly Jesuits, Franciscans, Augustinians, and Dominicans), but most importantly to the inability of the Portuguese to separate religion from trade, and to abdicate of missionary work exclusively in favour of trade.

Much of trade proceedings would have been allocated to the spread of the religion and humanitarian purposes like healthcare. (ibidem p. 55 and 125) European competition first from Spain, and later from the Dutch and the British would not have helped either. (Costa 1993, p. 56)

Charles Boxer, on the other hand, arguments that “the Jesuits were under no illusion about the reason for Ieyasu’s reluctant tolerance of their presence in Japan. It was simply and solely due to his conviction that they were indispensable intermediaries for the smooth functioning of the Macao-Nagasaki silk trade.” (Charles R. Boxer 1993 (1951), p.308)

For Boxer “[i]t will be apparent that the rivalry between the various Roman Catholic orders in Japan was one of the prime causes of the ruin of their missions just as it was two centuries later in China.” (Ibidem p.247) On top of this, it could not have been very helpful to the success of the Catholic mission that “[t]he mutual dislike of Portuguese and Spaniards was evidenced in a hundred ways in Japan.” (Ibidem p.238)

This author also calls our attention to the fact that according to his research “many of the local Portuguese merchants were married to Japanese women, and not merely living with them as were the heretics at Hirado. The Portuguese sailors were likewise better behaved that the north European rivals, iuf only because of Latin abstemiousness as opposed to Anglo-Dutch thirst for liquor.” (Ibidem p.306)

“The missionaries founded various congregations of Japanese, like the Confraria da Misericórdia, who looked after old people, orphans, refugees and who worked in hospitals and leprosaries; they took charge of cemeteries, funerals, helped prostitutes and supported the families of those who had died for the Faith.” (Matsuda 1965, p.99)

They also fought slavery (Matsuda 1965, p.99-100) and infanticide.

“The [Catholic] Church [in Japan] fought against bribery, gambling, usury, birth control, abortion, divorce and keeping of concubines. By persuading the Japanese to accept monogamy, the Church raised the status of Japanese women and made them aware of their power.” (Matsuda 1965, p.100)

“The persecution and prohibition of Christianity from the end of the sixteenth century and the Tokugawa policy of sakoku [or closed country][6] that largely closed Japan to foreign contact from the 1630s saw the decline of Namban art.” (Wikipedia, as accessed January 14, 2015)

Concentrated in the South however, around 1.2 million Catholics would survive/remain in current day Japan. (Soares 1997, p. 338)

“The Portuguese were the first to translate the Japanese to a Western language, in the Nippo Jisho dictionary (日葡辞書, literally the “Japanese-Portuguese Dictionary”) or “Vocabulario da Lingoa de Iapam” compiled by the Portuguese Jesuit João Rodrigues, and published in Nagasaki in 1603, who also wrote a grammar “Arte da Lingoa de Iapam” (日本大文典?, nihon daibunten).” (Janeira 1988, p.92 and Wikipedia, as accessed January 14, 2015) Rodrigues was of “exceptional linguistic skill, and nicknamed ‘Tçuzzu’, or interpreter…” (Boxer 1993, p.153)

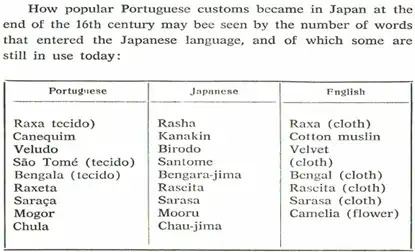

Today still more than fifty Japanese words derive from Portuguese, like botan, and some Portuguese ones derive from Japanese, as above mentioned ‘biombo’ and ‘catana’ for a specific type of sword. Others like Luís Filipe Thomaz (1993, p.24) mention “some two hundred Japanese words” of Portuguese origin, while Portuguese would have inherited “about thirty Japanese terms”. Among which Thomaz (1993, p.128-9) mentions biombo, bonzo, catana and sacana.

This author goes so far as to write: “Perhaps in no part of the globe, outside the domains of Portugal, was Portuguese influence so marked.” (Thomaz 1993, p. 24) Thomaz goes on to state: “The Japanese were, without a doubt, the people which, taken as a whole, aroused in them [the Portuguese] the greatest admiration.” (Thomaz 1993, p.57)

Nagasaki would have been founded by the Portuguese in a unique hilly setting by a deep water bay. [7]

[1] João Paulo Oliveira e Costa “O Japão e o cristianismo no século XVI. Ensaios de história luso-nipónica”, Sociedade Histórica da Independência de Portugal, Lisboa, 1999, p.34

[2] João Paulo Oliveira e Costa “A descoberta da civilização japonesa pelos portugueses” Instituto Cultural de Macau/Instituto de História de Além-Mar, 1995 (Master degree dissertation submitted 1988), p.62

[3] Janeira (ibidem p.62) mentions 1638 as the year of the third and last order of expulsion against the Portuguese and 1640 as the year of introduction of a sort of inquisition against the Christians. In 1624 permanent residence by the Portuguese in Japan would have been forbidden. (ibidem p.60)

[4] The first Dutch ship appeared in Japanese water in 1600 and “[t]he heretic Hollanders speedily received the name of Komojin or Red Haired Barbarians to distinguish them in Japanese (and Chinese) eyes from their Nambanjin or Southern Barbarian rivals of Portuguese India and the Philippines.” (Boxer 1948, p.48)

[5] Kiichi Matsuda “The Relations Between Portugal and Japan”, Junta de Investigações do Ultramar and Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, Lisbon, 1965, p.58

[6] “After various Western diplomatic missions had failed, an American squadron under Commodore Perry in 1853 succeeded in persuading the open Japan’s ports to foreigners. Merchants of many nations poured in.” (Boxer 1993, caption to plate 36). “The prohibition of Christianity was ended in 1873; new churches appeared among established temples. In 1927, a monument was erected to the Nagasaki martyrs. Christianity has become an accepted element in Japanese life.” (Boxer 1993, caption to plate 37-9)

[7] Armando Martins Janeira, “O impacto português sobre a civilização japonesa” Dom Quixote, Lisboa, 1988 (1970), p.181-185

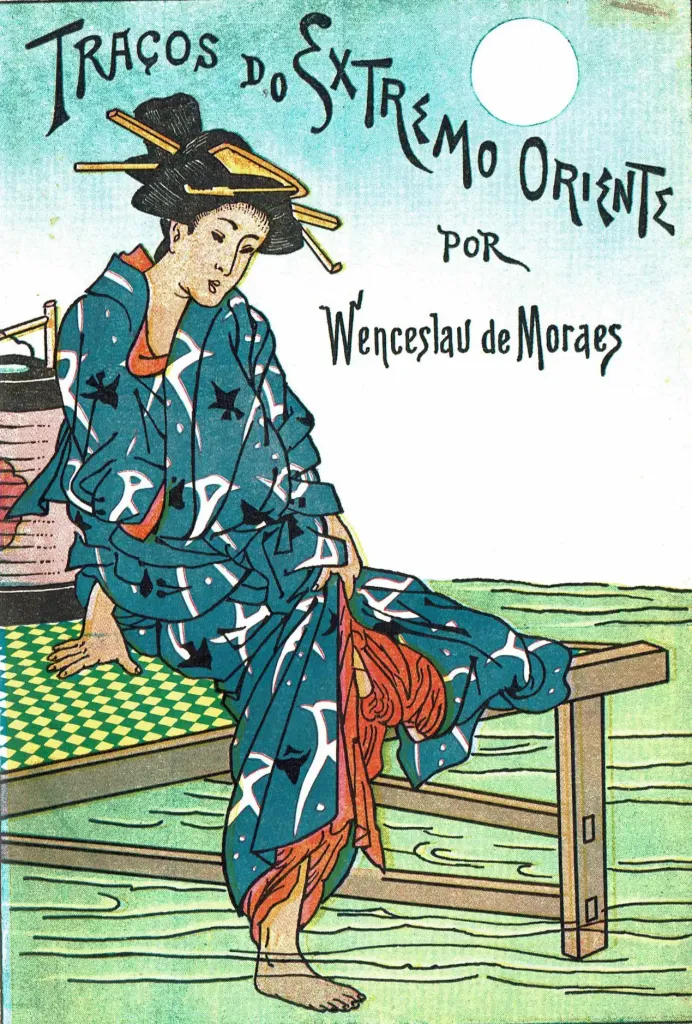

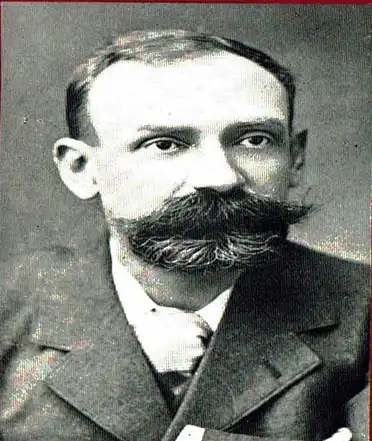

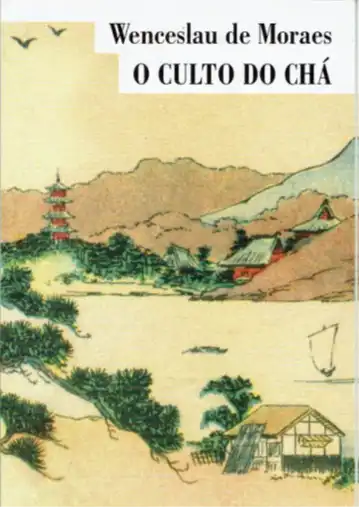

In this context, Wenceslau de Moraes (also Morais, Lisboa 1854 – Tokushima 1929) should not go unmentioned, as a prominent promoter of Japanese culture, and specifically of its ‘tea cult’.[1]

In his preface to this work Armando Martins Janeira calls our attention to the curious and perhaps meaningful fact that in the second half of the 16th century, Sen Rikyu, the greatest of all tea masters (chájin) and the one who gave the tea ceremony its definitive form, would have attended Catholic mass more than once, attentively observing the lithurgic ritual, whence he adopted and incorporated several gestures in the tea ceremony (chá-no-yu) as we know it today.[2]

Consul in Kobe from 1898 to 1913, he was merried to a Chinese, while previously in Macao, and consecutively to two Japanese women, and assimilated into Japanese culture and way of life. “He converted to Buddhism” and “has been compared to Lafcadio Hearn, a contemporary who settled in Japan but wrote in English.”[3]

[1] Wenceslau de Moraes “O culto do Chá”, Vega, 1996 (Kobe, 1905)

[2] (ibidem p.9) On page 10 of his preface Janeira refers us to João Rodrigues (Sernancelhe, 1561 or 1562 – Macao, 1633 or 1634) for an analysis of sociological aspects of the Japanese tea ceremony.

[3] From Wikipedia, as accessed July 2019.

Consul in Kobe from 1898 to 1913, he was merried to a Chinese, while previously in Macao, and consecutively to two Japanese women, and assimilated into Japanese culture and way of life. “He converted to Buddhism” and “has been compared to Lafcadio Hearn, a contemporary who settled in Japan but wrote in English.”[3]

[1] Wenceslau de Moraes “O culto do Chá”, Vega, 1996 (Kobe, 1905)

[2] (ibidem p.9) On page 10 of his preface Janeira refers us to João Rodrigues (Sernancelhe, 1561 or 1562 – Macao, 1633 or 1634) for an analysis of sociological aspects of the Japanese tea ceremony.

[3] From Wikipedia, as accessed July 2019.

As a profound admirer of what he considers authentic Japanese culture Wenceslau de Moraes does not devote much of his attention to the presence of the Portuguese in Japan over the 16th and 17th centuries. Actually I was only able to trace one section of one of his several writings to the ‘vestiges of the passage of the Portuguese through Japan’, namely from his original book “Os serões no Japão” originally published in 1905 and reproduced as a chapter in the 2008 edition of his “O Culto do Chá”.

According to him, “Japanese leaders should not condone such a large moral influence by strangers, which would lead to the disintegration of the Japanese family, to fanatism, to religious oppression, to inquisition and certainly, at the end of the day, to the political domination by the whites over Mikados’ soil.”[1]

[1] The author’s own translation of a sentence in “O Culto do Chá” , Relógio d’Água, Lisboa, 2008, p.71

Another Portuguese personality worth mentioning in this context, and already mentioned above, is João Rodrigues (1561?, Sernancelhe, Nossa Senhora da Lapa – 1633, Macao), the Tçuzzu[1], or the Interpreter.[2]

“…few men have led a more eventful life during more portentous times. During more than half a century in Japan and China, Rodrigues won the friendship of Japan’s two successive supreme rulers, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu; took an active role in the silk trade between China and Japan; and, serving as the principal interpreter between East and West, was for some years the most influential European European in the entire country. He witnessed both the early successes of Christianity in Japan and the first fierce martyrdoms, which heralded the religion’s complete proscription.

Fluent in Japanese, he somehow found time to compose the first grammar of the language ever to be published[3], and in his old age he wrote a lengthy account of Japanese culture that has astonished modern readers by its discernment and wealth of detail.

In China, he travelled widely, was involved in heated argument over how far Catholic missionaries should accommodate their teachings to Oriental customs, conducted official business on behalf of Macao, and took part in military skirmishing between Ming defenders and Manchu invaders, And in China he died, still longing for the Japan from which he had been exiled by cunning intrigues.”[4]

“Among the Europeans who were obliged to retreat hastily back to Bungo along with Ōtomo and the remnants of his shattered army was a seventeen-year-old Portuguese boy. His name was João Rodrigues.”[5] “Nothing is known about Rodrigues’ family and childhood in Portugal.” Only that he “left Portugal at the age of 13 or 14, perhaps even younger, and never returned” and that he “came to Japan as a child in 1577.”[6]

“Apart from a brief visit to Macao in 1596 Rodrigues spent thirty-three consecutive years in Japan, during which time he travelled extensively and visited different parts of the country. But Nagasaki was to be his principal base of operations, especially in the latter half of his career in Japan, and he personally witnessed the growth and development of the city.”[7]

“Whatever the precise date of his arrival in Peking[8], Rodrigues was most probably the first European to visit the capitals of both Japan and China.” (Cooper 1974, p.280)

Luis Fróis (Lisboa 1532 – 1597 Nagasaki) is credited with, “based on first-hand experience gathered during a … more than twenty years experience and with a deep knowledge of the language, and the ways of thinking and behavior of the people” to have “drafted the earliest systematic comparison of Western and Asian cultures.

[9] “What is significant is Frois’ explicit recognition that one need not think and behave as a European to be civilized.”[10]

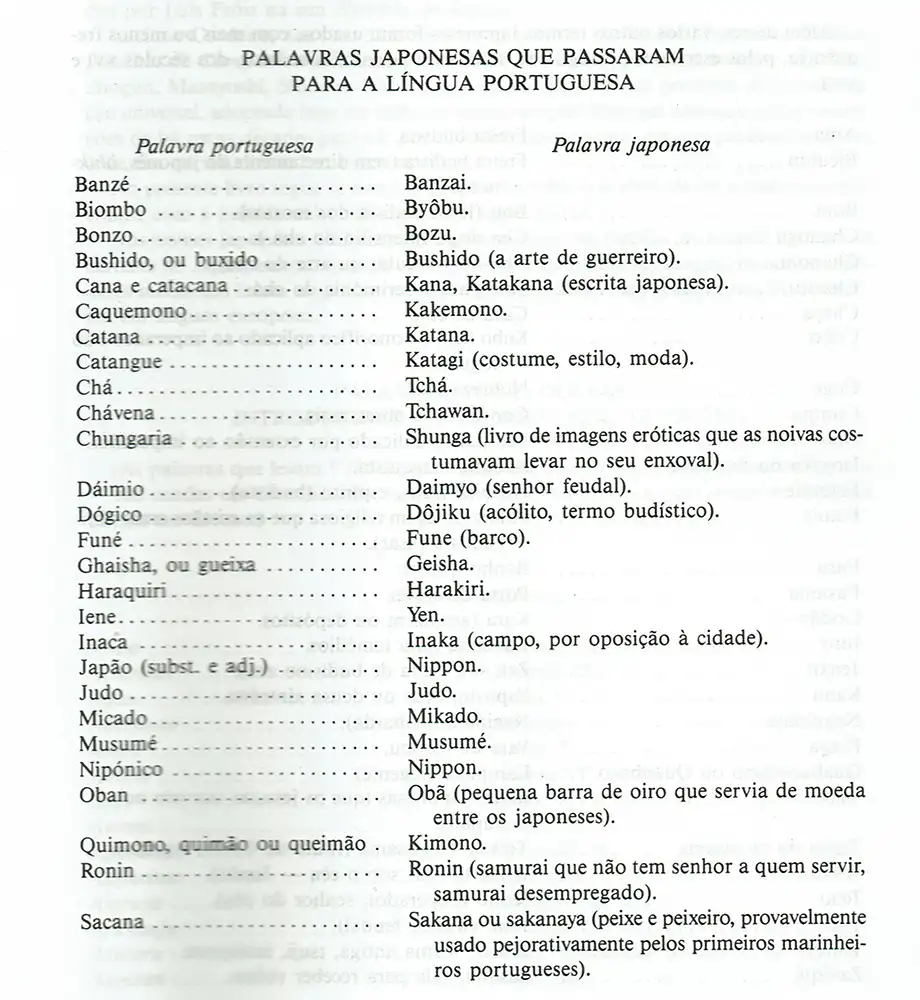

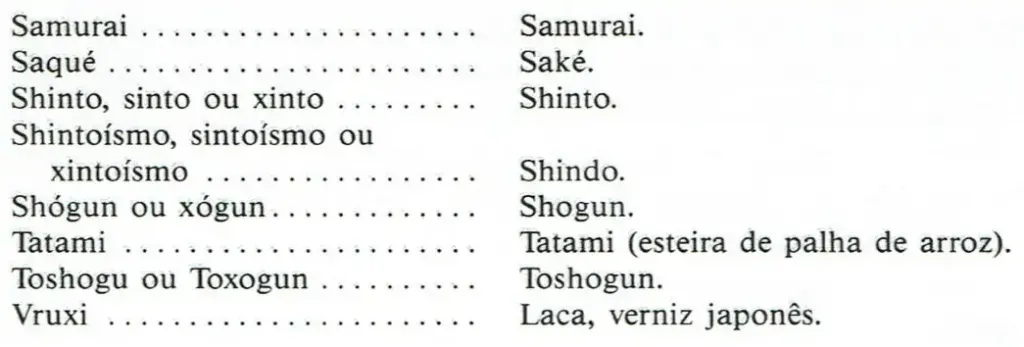

Armando Martins Janeira[11] lists following “Japanese words, which would have passed into the Portuguese language”:

[1] Derived from the Japanese word tsūji, interpreter. Michael Cooper “Rodrigues the Interpreter. An Early Jesuit in Japan and China”, Weatherhill, New York & Tokyo, 1974, p.69

[2] For an insight in French into this you may grab Jacques Bésineau’s “Au Japon avec João Rodrigues, 1580-1620” Centre Culturel Calouste Gulbenkian/Commission Nationale pour les Commémorations des Découvertes Portugaises, Lisbonne/Paris, 1998

[3] “Arte da Lingoa de Iapam”, Nagasaki, 1604 or 1608, according to Cooper 1974, p.224. Previous grammars had been composed by other Jesuits since 1564, but “the Japanese themselves had never undertaken a systematic study of their own tongue, and Rodrigues’ grammars mark the beginning of a methodical exposition of the spoken language.”

[4] From the flaps of Michael Cooper’s book.

[5] Cooper 1974, p.19

[6] Cooper 1974, p.20, 22 and 23

[7] Cooper 1974, p.38-39

[8] Allegedly 1615 (Cooper 1974, p.280)

[9] Luis Fróis “The first European description of Japan, 1585. A critical English-language edition of Striking Contrasts in the Custom of Europe and Japan. Translated from the Portuguese original and edited and annotated by Richard K. Danford, Robin D. Gill and Daniel T. Reff, with a critical introduction by Daniel T. Reff”, Routledge, London and New York, 2014

[10] From Reff’s critical introduction to Luis Frois (2014), p.3 and 16. You may also read Luis Fróis “Europa Japão. Um diálogo civilizacional no século XVI”, Comissão para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, Lisboa, 1993 (“Tratado em que se contêm muito sucinta e abreviadamente algumas contradições e diferenças de costumes entre a gente de Europa e esta província de Japão…1585) with an introduction by José Manuel Garcia

[11] 1988, p.215-6

“Of Portuguese words which which have survived in the vernacular to this day, the best known are tabako (tobacco); kappa (capa, a straw raincoat), karuta (carta, playing card); kompeito (confeito, confits, sweets, or jam), and biidro (vidro, glass), but there were many others which are now obsolete.” (Boxer 1993 – 1951, p.208).

The same author gives us an extensive list of Portuguese words, which would have found their way into the Japanese vocabulary.[1] Soares (1997, p. 339) estimates their number at around 200; Matsuda (1965, p.92-93) lists 37 of them. (See below)

[1] 1988, p. 217-225