Luso-American Links

Interactions between the two countries go way back to the early beginnings of what was to become the United States of America.

Some of the readers who might have attended the outdoor drama, The Lost Colony, will have been confronted with the only two villains in the play: Wanchese, a treacherous Indian, and Simão Fernandes, the not less treacherous Portuguese “pilot on all 3 major Roanoke expeditions, as well as [John] White’s archnemesis. More than any other single person, he is blamed for the failure of the governor’s colony after refusing to carry the settlers north to the Chesapeake.”.

Fernandes was born around 1538 on the island of Terceira in the Atlantic Azorean archipelago, emigrated to England, converted to the Church of England, married a local woman, became a naturalized citizen, and afterall “we have more detail about Fernandes’s life and exploits than White’s and Lane’s combined. In fact, he was better travelled than and more cosmopolitan than [Walter] Raleigh, [Richard] Hakluyt, or [Thomas] Harriot.

He also worked for or knew many of the most powerful courtiers of Elizabethan England. And he [even] could write. [sic] Though there is no known portrait, we have a fleeting glimpse of the villain on Roanoke. He wasn’t the tall, dark, and unabashedly sinister figure of the Lost Colony drama, where he struts about the stage kicking dogs and frightening children. A Spanish sailor described him as ‘bald of the head, blond, of medium thick body’.” (ibidem p.210) I leave to the reader the interpretation of what might be behind this drama rendition…

You might also wonder what was the business of a Portuguese pilot on board of these ships carrying the first colonists from England to North America. It so happens that “Portuguese pilots, considered the best in the world [by then], were in high demand. … and Fernandes might have taken part in a 1566 Spanish [?] voyage to the Outer Banks piloted by Domingo and Baltasar Fernandes, two Portuguese pilots who were possibly older relatives.” (ibidem p.214) “Fernandes … was present at the first meeting with the Native Americans on the Outer Banks beach in 1584”, perhaps because “Portuguese pilots were far more than just hired drivers.

They were also known for their ability to serve as mediators with Native Americans in the New World.” (ibidem p.220)

To some, like Pedro Diaz, a contemporary Spanish pilot captured by the English and later interrogated by Spanish officials, Simão Fernandes was not only a ‘skillful pilot’ but ‘the author and promoter’ of the Roanoke venture’. (ibidem p.224) Further than that: “Long after he vanished off the Azores aboard an English fleet in 1590, Fernandes may have played a critical role in founding Jamestown and ensuring his adopted country’s foothold in the New World.” Someone warned this author that perhaps he was going too far. But … (ibidem p.227)

According to James Alexander Williamson, it is also “necessary to take account of the doings of the Portuguese, since their undertakings in the years 1499-1503 had an influence upon the Bristol adventurers and have also left a rich legacy of cartographical material.” He goes further: In the Azorean island of Terceira there lived in the last decade of the fifteenth century a small squire or landowner named João Fernandez.

His status is described by the Portuguese term llabrador. The word is of some consequence, for it is likely that he was the man whose social description became a proper name which, after some vicissitudes, is now attached to the north-eastern coast of America, …” (ibidem p.198)

“Gaspar Corte Real sailed northwards from Lisbon without delay, and in June, 1500, reached the east coast of Greenland.” (ibidem p.202)

“Early in 1501 three Azoreans, João Fernandez, Francisco Fernandez and João Gonsalvez, were engaged in a plan of discovery with three Bristol merchants, Richard Warde, Thomas Asshehurst and John Thomas.” (ibidem p.204) “The three Azoreans and their children are accepted as the king’s naturalized subjects for all legal purposes except the payment of customs and subsidies, for which they shall continue in the status of foreigners.” (ibidem p.205)

“The model [of the royal patent granted to them] appears to be drawn from the Portuguese patents of the fifteenth century, and we may reasonably regard João Fernandez and his friends as in some small sense among the founders of our imperial polity.” (ibidem p.206) Williamson concludes tht it “seems probable thst the grantees of 1501 intended to push north-westward from Newfoundland up the coast of Labrador. That being so, it is highly likely that they were in search of the North West Passage and realized that the new land was not Asia.” (ibidem p.206-7)

Modern Portuguese migration to the USA started late 18th – early 19th century, when the US whaling fleet tok on board mostly Azorean and Madeira sailors and fishermen, who went on land when the first opportunity arrived. They settled down first on the East Coast, namely Massachussets, and Rhode Island, where they dedicated their energy to the fishing industry first, and later to the local manufacturing industry. Newark, NJ, was also an important settling space.

Soon however, many followed suit around the Cape Horn, over the Panama straight, or – a minority – over land to the West Coast, where they first stuck to fishing related activities, namely whaling, but soon also moved inland and dedicated themselves to raising cattle, dairy farming, and to agriculture related activities.

“It is on record that in the year 1780 men of Faial, Pico, S. Jorge, Flores and Corvo in the Azores embarked as members of the crews of two hundred whalers, which had anchored in the Azores, and proceeded later to the United States. It is further presumed that the Portuguese established themselves between 1789 and 1815 in Upper California and founded various whaling stations at Half Moon Bay, Pescadero, Monterey, Carmelo, San Simeon, Point Conception, Portuguese Cove, Portuguese Bend and San Diego.

At Monterey the building of the ‘Portuguese Whaling Station’, founded in 1850, still existed recently. After the discovery of gold in California in 1848 or, as others suppose, from the year 1860 immigration into the State of California grew steadly and gave rise to our present very important settlements.

Although, as we have remarked, the Portuguee devoted themselves mainly to fishing, formerly of whales and now of tunny, and, to agriculture, especially to the production of milk, we find Portuguese and their descendants in every branch of activity.”

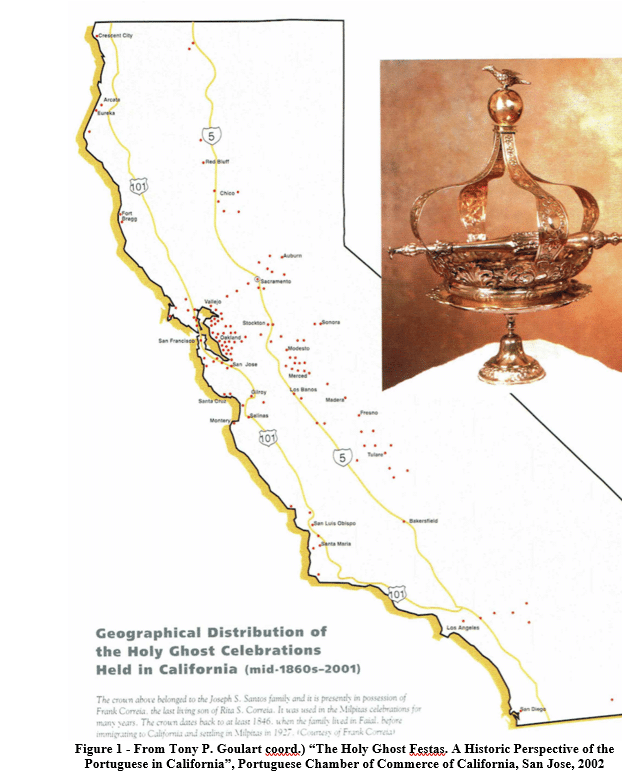

They have taken with them many of their ancestral customs, namely religious ones as the Holy Ghost/Spirit festivities. For almost 140 years, more than 160 celebrations were held in approximately 130 cities and small towns throughout the state.

João Rodrigues Cabrilho, who died at the Azorean island of San Miguel 1543, would have been the first European to explore the California coast, namely San Francisco and San Diego, even if in the service of the King of Spain in the year of 1542.