The Legacy of Asia

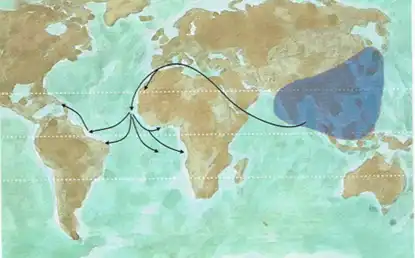

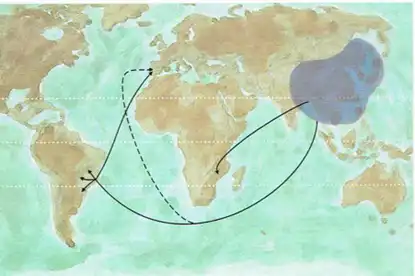

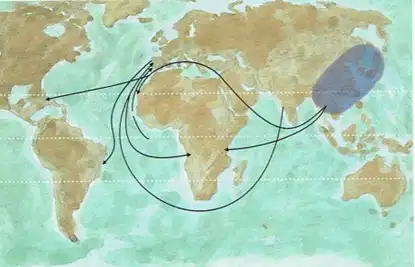

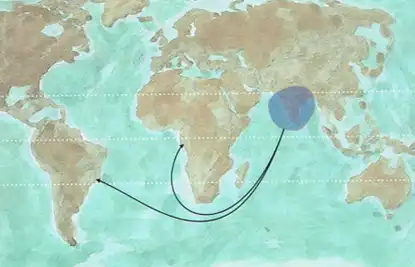

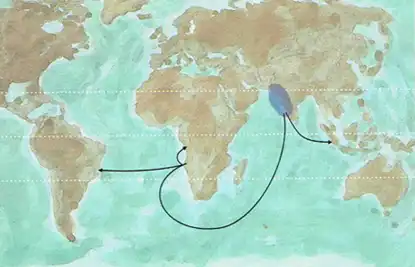

“For crop transferences between Asia and Africa and America, the Portuguese are again presumed to have been largely responsible. To them, for want of other evidence, are attributed the introduction of coconuts and Asiatic, rice to West Africa, of eddoes (Colocasia) to America, and the fact that in India such American plants are recorded as pineapples in 1583, papaya in 1600 and sweet potatoes in 1616.” (Masefield 1967, p.286)[1]

- Arroz/rice, some species of which already existed in Africa and America prior to the Portuguese discoveries. “White or Asian rice was already known in the Mediterranean before the Discoveries. … It is thought that rice was brought from Portugal to the islands of Cape Verde, and from there to Brazil, but it may well have come from Orient via Cape Verde.” (Ferrão 2005, p.182)[2]

[1] For a thorough review of plant translocation between continents in which the Portuguese have been instrumental, if not pioneers, in the context of their discoveries, you may read both main works of José E. Mendes Ferrão (“A aventura das plantas e os descobrimentos portugueses”, 2005 (3rd edition), with short abstracts in English, and its sort of abridged version “Plantas nos descobrimentos portugueses nos séculos XV e XVI”, Universidade Católica Editora, Lisboa, 2015), who in this later one states that “in world terms, the efforts with the discoveries would have been worth it, if only for the influence exerted by the plants they helped spread across the continents.

[2] José E. Mendes Ferrão, “A aventura das plantas e os descobrimentos portugueses”, 2005 (3rd edition)

- Mediterranean region before the Portuguese Discoveries. The Portuguese introduced the banana to the Atlantic islands of Africa and to the West Coast of Africa south of Gambia. The banana was already being cultivated on the East Coast of Africa when the Portuguese arrived.” (Ferrão 2005, p.187) “References exist, although they are much disputed, suggesting that bananas already existed in America before the arrival of Spaniards and Portuguese. … All references suggest that the banana was introduced to Brazil via São Tomé after the Discoveries.

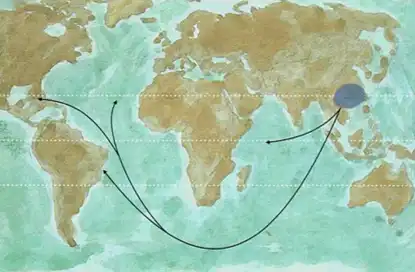

- Tea/chá. “Portuguese missionaries were perhaps the first Europeans to report on tea, and the Dutch sea merchants introduced the brew to Europe.” (Wolf 1982, p.339)[1] This is corroborated by Masefield (1967, p.297)[2], who dates the Dutch introduction of tea into Europe at 1610. “[D]uring the last third of the [seventeenth] century it became the predilection drink of English court circles.” (Wolf 1982, p.339) And some say that Catarina de Bragança’s marriage to Charles II 1662 played a role in this.[3]

[1] Wolf, Eric R. “Europe and the People Without History”, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1982

[2] Masefield, G. B. “Crops and Livestock” in “The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, vol.IV, The Economy of Expanding Europe in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”, Cambridge University Press, 1967, 275-301

[3] For a somewhat skeptical insight of this hypothesis you may see Flor, Susana Varela “’The Palace of the Soul Serene’: Queen Catherine of Braganza and the Consumption of Tea in Stuart England (1662-1693)”, e-JPH, vol.19, number 2, December 2021, p.171-191

The Portuguese are among the few, if not the only Europeans that use a different original Chinese expression “chá”, instead of tea and its derivatives. Cockney English uses cha or rather char too. “The Portuguese probably first came across the drink in the Canton region, and used the local word (ch’a). Later, other Europeans encountered it in the Tonkin region and also adopted the local word (t’e). As is commonly alleged, tea as a beverage was introduced to the English court by the Portuguese queen D. Catarina de Bragança, daughter of King João IV, which leads one to believe that it was already known in Portugal at that time, although it was far from widespread. … there are records of tea plant’s existence in Angra do Heroísmo, in the Azores, at the beginning of that [nineteenth] century, and its introduction to Brazil at the beginning of the nineteenth century is confirmed – although the date is open to question – when King João VI travelled to Rio de Janeiro as a result of the French invasion, and received tea plant as a gift from the Chinese emperor. From Brazil tea then reached the Island of São Miguel in the Azores, and continental Portugal, where attempts were made to grow it in the north, centre and south. “ (Ferrão 2005, p.200)

- Citrus plants “originated in South-East Asia. They were brought to Europe by the Arabs and were already known in the Mediterranean region and Portugal long before the Portuguese Discoveries. Some authors claim that the sweet orange was brought to Europe by the Portuguese, but that is only partially true and is unrelated to the introduction of the species. … in 1635 an Orange tree was brought from China to Goa, and from there to Portugal giving rise to the name ‘China oranges’ in the later country, which was a synonym of very sweet oranges. From that orange tree oranges spread throughout the Mediterranean, where there is a striking similarity between the names of Portugal and orange in the languages of the countries which border that sea.” (Ferrão 2005, p.207) Po(u)rtugalié in Nice, Portugalet(t)o in the Piemonte, Portukale(na) in Albania, Portugalis in Greece, Portughal in Kurdistan, and also in Turkey and Romania.

Portugal and orange are synonymous, according to Luis Pedro Nunes (“Jesus nunca comeu uma manga…”, in Público, Feb.21, 2025), also in Arabic. Nunes also mentions several other traces of the role of the Portuguese in the diffusion of many other fruits and other vegetables across the globe.

- The coconut “originates on the islands of Polynesia or South-East Asia. Some authors suggest it has its origins in America, or at least that the coconut already existed there before the Europeans arrived. These two points of view have not achieved wide acceptance and are based on the fact that the Portuguese first encountered the coconut in India and introduced it to Cape Verde and America in an unusual way. The Portuguese appear to have learned from Oriental seafarers that carrying coconuts aboard ship was a useful source of fresh food and water, being easy to keep and of enormous value on long voyages. Either intentionally, or simply using the coconuts they did not consume, they sowed coconuts in Cape Verde at the beginning of the sixteenth century.” (Ferrão 2005, p.211) “Gabriel Soares de Sousa mentions that the first coconuts reached Brazil from Cape Verde, ‘from where they spread throughout the world’. The Portuguese found the coconut palm already growing on the East African coast, according to descriptions provided by the Via do Conde Pilot.” (Ferrão 2005, p.211-2)

Bread fruit “originally came from Malaysia, and by the time of the Portuguese Discoveries had already spread throughout South-East Asia and the Pacific islands. “(Ferrão 2005, p.214) “It was introduced in America (Jamaica) in 1793 by Captain Bligh, the introduction being linked to the famous mutiny of the crew of the Bounty. The Portuguese introduced it to Brazil, at a date we have as yet been unable to ascertain.” (Ferrão 2005, p.214)

- Jackfruit “originates in the East, possibly India, and was found throughout that great region, wherever the ecological conditions permitted, before the Europeans arrived. … It was introduced into Brazil by the Portuguese.” (Ferrão 2005, p.216)

- Lychees “originate in Southern China, where they have been grown for over thousand years, but they remained virtually unknown in the West and even in the regions bordering China. The first known reference to the plant in Western writings is from 1585, through Mendonça and his history of China.” (Ferrão 2005, p.219)

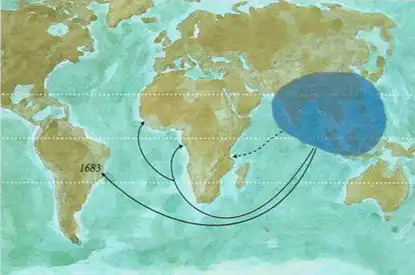

- Mango “originates in the Orient (India, Burma and Malaysia), and is regarded as one of the finest tropical fruits. … Unless prior evidence exists which we have still to unearth, the mango was introduced to America by the Portuguese at the end of the seventeenth century. As it was normal, some plants were of course left on the West African coast at the same time.” (Ferrão 2005, p.225)

- Cinnamon is originally from the Island of Ceylon, where cultivation was concentrated until the sixteenth century. To corner the cinnamon trade, the Portuguese occupied the Island in 1518, after having visited it in 1506 and seen how rich in cinnamon it was. … It is thought that as early as the sixteenth century the Portuguese had already introduced cinnamon to Brazil, possibly brought by Jesuits.” (Ferrão 2005, p.231)

- Clove is “originally from the Moluccas (Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian and Batjan). … For many years production was limited to these islands, during both the Portuguese and the subsequent Dutch occupation.” (Ferrão 2005, p.239)

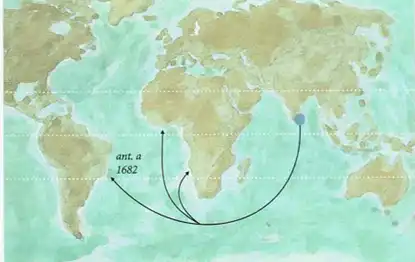

- Ginger “originally from tropical Asia, … has been known in India and China since ancient times. … When the Portuguese reached India, the plant was already widespread in the Orient, and all indications are that it was also already being grown on the East Coast of Africa. It was introduced to São Tomé by the Portuguese, where it grew well, and to Brazil, where according to Gabriel Soares de Sousa it spread rapidly. Production increased to such an extent that it was banned in those two places because of the competition it represented to Indian production, but that ban was later lifted, at least in part. There were successive introductions of ginger to Brazil from India during the seventeenth century, when the aim was to recreate in America the spice-producing centre the Portuguese had lost in the Orient.” (Ferrão 2005, p.242)

- Pepper “is originally from South-East Asia. The Portuguese discovered the spice on the East African coast during the voyage of Vasco da Gama, in Malindi and Mombasa, according to the Anonymous Pilot. It was produced in great quantities in the area between the Ghats and the west coast of Indian subcontinent, … All indications are that, as with other spices, pepper was introduced into Brazil at the very start of the sixteenth century.” (Ferrão 2005, p.250-1)

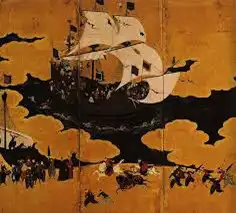

- “The first documented introduction of the matchlock, which became known as the tanegashima, was through the Portuguese in 1543. The tanegashima seems to have been based on snap matchlocks that were produced in the armory of Goa in Portuguese India, which was captured and occupied by the Portuguese in 1510. The name tanegashima came from the island where a Chinese junk with Portuguese adventurers on board was driven to anchor by a storm. The lord of the Japanese island Tanegashima, Tokitaka (1528–1579) purchased two matchlock muskets from the Portuguese and put a swordsmith to work in copying the matchlock barrel and firing mechanism. Within a few years the use of the tanegashima in battle forever changed the way war was fought in Japan.” (from the Wikipedia “Firearms of Japan”, as accessed February 27, 2014)

- Besides firearms and Christianity, and throughout the latter half of the 16th century and into the 17th, Portuguese traders sold Japanese as slaves overseas, so that “toward the end of the 16th century, a large number of Japanese were in several parts of Asia … They were found in the regions where Portugal was dominant as a colonial power, such as India, southeast Asia, and southern China, particularly in Macao, around the Strait of Malacca and in Goa, India.” (Michio Kitahara “Portuguese Colonialism and Japanese Slaves”, Kadensha, 2013 and Rafael G. Antunes “Os últimos portugueses de Malaca”, in Expresso, Revista E, August 29, 2025).

- The Portuguese language was the first instrument of communication between Japan and the West. Other foreigners were obliged to use it in their relations with the Japanese. The Jesuit João Rodrigues was the author of the first grammar of the Japanese language, Arte de Lingoa de Iapan (Nagasaki, 1604-1608), which is consulted to this day by Japanese experts who want to know the history of their language.

The Wikipedia lists around fifty Japanese words of Portuguese origin (as accessed February 28, 2014). This adoption was the result of the so-called Nanban trade period, which occurred from 1543 to 1614, during which these “southern barbarians” engaged in rather significant commercial exchange with neighbouring and farther away shores, which was at the origin of the Nanbanga, or Nanbanbijutsu, art style which “designates the numerous pictorial representations that were made of the new foreigners and defines a whole style category in Japanese art.” (from the Wikipedia, as accessed February 28, 2014)

- “Sirih kaya is a desert/sweet dish of the Malays introduced to Sri Lanka through the Malay diaspora.” (Jayasuriya 2008 p.68) It also happens to be a popular desert in nowadays Portugal.